With increasing regularity, Earth’s oceans are the drop zones for incoming leftovers from space.

For decades, Russian Progress resupply spacecraft loaded with tons of waste from the International Space Station (ISS) have been intentionally steered to reentries over the Pacific Ocean’s “spacecraft cemetery.” Similarly, Northop Grumman’s Cygnus cargo vehicles are filled with rubbish from the space station crew and ultimately ditched over the South Pacific.

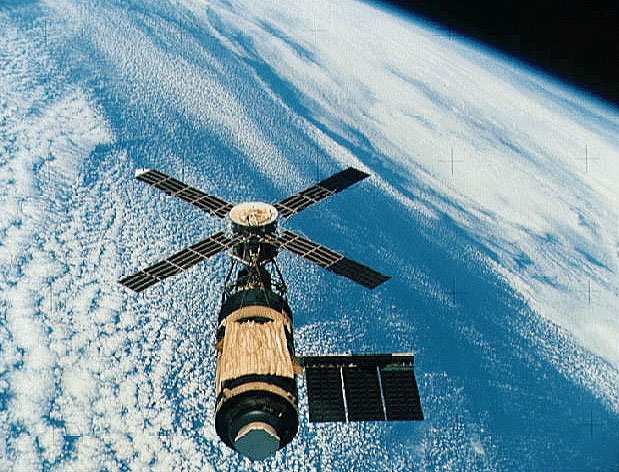

In the past, other discarded orbiting facilities — such as Russia’s Mir space station and China’s Tiangong-1 prototype outpost — ended their lives over ocean waters. Then there’s the saga of America’s Skylab experimental station, which fell to Earth in 1979, with odds and ends scattering across the southern Australian coast.

Skylab: The first US space station

And a huge piece of falling space junk will come back to Earth in the not-too-distant future — the nearly 500-ton ISS. The plan is to bring the ISS down in a controlled fashion over the South Pacific Oceanic Uninhabited Area, a region around Point Nemo formally known as “the oceanic pole of inaccessibility.”

This remote sea setting is about 1,450 nautical miles (2,685 kilometers) from the nearest piece of dry land. The closest terra firm is Ducie Island, part of the Pitcairn Islands, to the north; Motu Nui, one of the Easter Islands, to the northeast; and Maher Island, part of Antarctica, to the south.

Is dumping space junk over Point Nemo a good idea? Or can we do better?

Non-traditional insult

Britta Baechler is senior manager of Ocean Plastics Research for the Ocean Conservancy, a leading group seeking science-based solutions for a healthy ocean and the wildlife and communities that depend on oceanic waters.

“From our perspective, it’s definitely concerning that the ocean is still being used in this way as a dumping ground,” said Baechler. “We can’t keep putting our waste into the ocean, expecting it to function the way it always has, for humanity and all life on Earth. In many ways, this is an out-of-this-world illustration of what’s been going on for so long.”

Baechler advised against viewing Earth’s ocean waters as “too big to fail” and stressed the need to look at the end-of-life scenario for everything that humanity makes. For instance, roughly 11 million tons of plastic pollution is being tossed into the ocean every year. That’s equivalent, she said, to a garbage truck dumping plastic into the ocean every minute of every day.

“Ingestion and entanglement with plastics in the ocean can also be a lethal encounter for a lot of different types of sea life,” Baechler said. Likewise, the dumping of tires, metals, toxic fuels and other refuse into ocean waters has spurred unforeseen issues and can provoke long-term consequences.

“Ultimately, it just doesn’t create a pretty picture,” Baechler said. Given the makeup of the ISS, inside and out, there is a need to understand the impact of the debris on the ecosystem and marine life, she added.

“This is another non-traditional insult to the ocean. It is a concern, and it’s not an appropriate use of the ocean,” Baechler counseled.

Planet Earth: Facts about our home planet

‘There is no other safe alternative’

Dwight Steven-Boniecki is the director of the feature film “Searching for Skylab, America’s Forgotten Triumph.”

“The only option for the ISS is deorbit,” said Steven-Boniecki. “Incidents of deorbited spacecraft are infrequent enough to not cause any major dilemmas when an ocean is used as the impact zone. Currently this is infinitely more preferable than trying to target remote land masses. Additionally, the friction of reentry conveniently ensures the bulk of the spacecraft is incinerated before it hits the ground/water. Choosing water as the landing zone provides a safe way to dispose of the debris. There is no other safe alternative.”

Steven-Boniecki said that, back in 1978-1979, the procedure of deorbiting spacecraft was relatively unknown. But one thing was certain, he said — the mass hysteria that the prospect of having a spacecraft fall on your head provoked.

“Skylab is arguably most remembered for falling out of the sky and crashing into the remote areas of Esperance, Balladonia and Rawlinna in Western Australia,” Steven-Boniecki said.

In 1979, NASA attempted to crash Skylab into the Indian Ocean, thereby avoiding any land mass altogether, Steven-Boniecki added.

“However, slight miscalculations resulted in portions of the space station impacting Western Australia a good 30 minutes after the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD) [now North American Aerospace Defense Command] declar[ed] Skylab as having impacted the Indian Ocean!” he said.

Legal issues

Disposing of the ISS involves a number of issues, said Joanne Irene Gabrynowicz, professor emerita and Journal of Space Law editor-in-chief emerita at the University of Mississippi School of Law.

Gabrynowicz flags Article 9 of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which notes, in part, that parties to the treaty are obligated to “avoid harmful contamination” of space, “harmful interference” with other signatories’ space activities and “adverse changes” to the Earth environment. All of these obligations are potentially applicable to an ISS return to Earth, she said.

A space object that has been to space and back, like the ISS, could carry some type of extraterrestrial contamination, or it could break into pieces, Gabrynowicz said. “There are qualifications here. But there is clearly a thought in the Treaty to protect the Earth and not to create adverse changes on our planet.”

Additionally, when the treaty was negotiated, the parties agreed there would be no salvage in space of space objects — a hands-off approach to short-circuit concerns of grabbing somebody’s hardware for military advantage.

“That’s not true in the ocean. There’s a very robust body of salvage law, including in international waters,” Gabrynowicz added. “Once the ISS is in the ocean, there’ll be people who want to grab that stuff.”

Related: Building the International Space Station (photos)

Setting a precedent?

Yet another legal issue concerns the ISS agreement itself, signed by multiple countries participating in the program. Each of the nations that have registered their components have ownership of those items.

“Though we are looking at one integrated space station, the individual component parts are also covered by legal requirements. That means they are all going to have to agree beforehand on how to dispose of the station,” said Gabrynowicz, “including specific provisions about liability.”

Whether “burning in” or not, the deorbiting of the ISS will require the partners to reach new agreements and some specifics regarding how liability is handled. “Then we’ll see if this is a space law, precedent-making event,” Gabrynowicz concluded.

Leonard David is author of “Moon Rush: The New Space Race” (National Geographic, 2019). A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.