Staring out into space is a time-tested technique for making long journeys pass more quickly, but not one often applied at the scale of the solar system.

That’s exactly the approach a team of scientists have turned to in hopes of someday launching a mission to a family of strange, icy bodies called Centaurs. Researchers had proposed a mission to NASA in 2019 that would fly by two Centaurs in the agency’s smaller planetary science mission class. NASA decided not to pursue the idea; eventually the process ended with the selection in June 2021 of two new missions to Venus.

But the scientists behind the mission idea weren’t ready to let go of it quite yet. “After you put together a spacecraft mission and you spend all that time thinking about how amazing it would be if you could do this, you’re still really excited about it,” Kelsi Singer, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado, told Space.com.

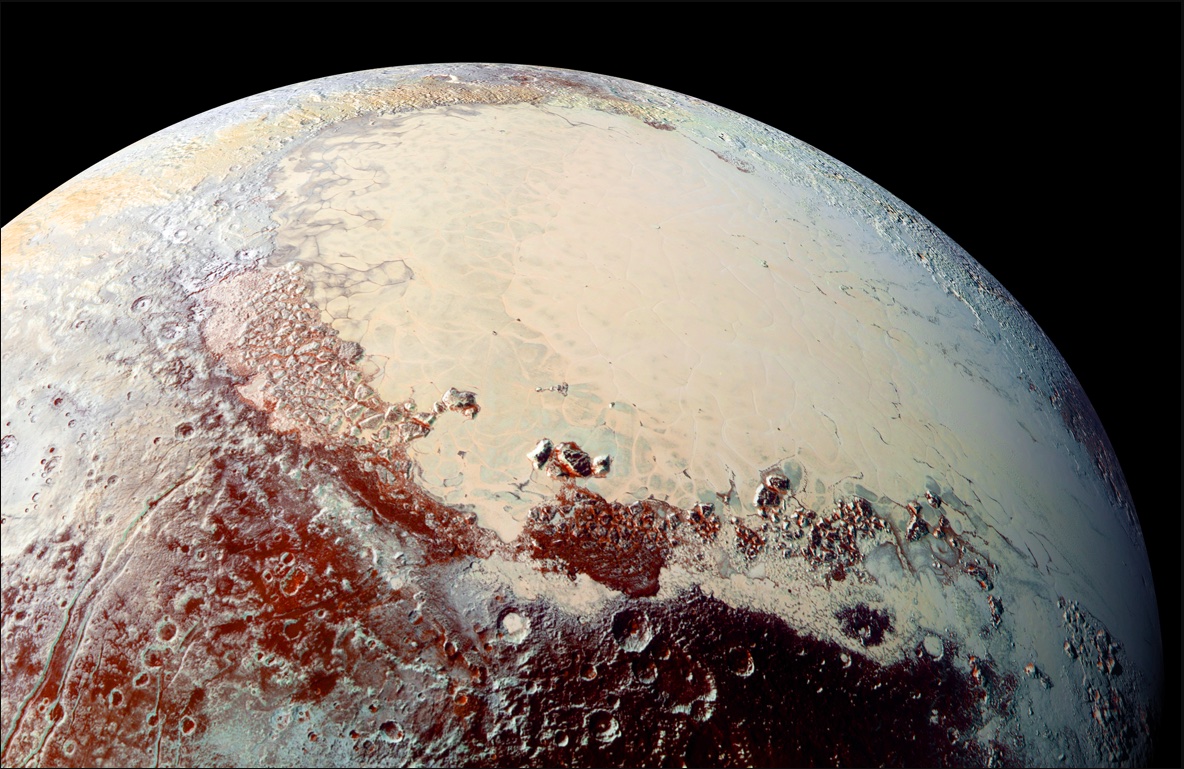

Related: The most amazing photos from NASA’s New Horizons mission

So Singer and her colleagues took another look at their idea and gave it an upgrade. They were confident about the science returns the mission could deliver and the importance of visiting Centaurs up close. But between flybys, the spacecraft had to make huge treks that left scientists without new data for as long as five years on end.

And cruising is not exciting. “It’s not our favorite part of the mission, let’s put it that way,” Singer said. The team had thought of some options to make the most of this time in the original mission concept, but decided to revisit the long cruises when they upgraded the idea.

“Then we realized that there’s such a high demand for space telescope time,” Singer said. “And that would also be a great way to fill the cruise time.”

Such a space telescope would need to be an additional instrument optimized for astrophysics, rather than a modified planetary science instrument, the scientists decided, to ensure everyone got worthwhile data.

A ride-along space telescope is not the usual model for spacecraft doing either planetary science or astrophysics, but Singer and her colleagues argue that their mission offers some real advantages even to scientists with no interest in the strange, icy Centaurs.

“There are some advantages to getting as far out as we would be going, and it’s just not very common to have a space telescope out that far,” Singer said.

For one, there’s no atmospheric interference to blur the view, of course, but that’s true of all space telescopes. What the journey to the Centaurs would offer uniquely is an instrument that might have a wider range of view and a different angle on objects in the solar system than, say, the Hubble Space Telescope trapped in orbit around Earth. In addition, dust in the inner solar system reflects light that a deep-space mission could avoid, sharpening its vision.

It’s not a system that would appeal to, or even be feasible for, all research. But it doesn’t need to be; it’s meant to boost science returns, not to replace NASA’s fleet of space telescopes. “We would want to not replicate something that’s already being planned,” Singer said. “We’d want to really try to fill a hole.”

Icy destinations

Even with the added astronomical work, the heart of the mission would remain the Centaurs. These objects got their name because they display characteristics of both asteroids and comets, reminding astronomers of the mythical beings that joined a human head and torso with a horse’s body.

Now, scientists know that Centaurs are more accurately described as a comet’s predecessor. “They’re basically Kuiper Belt objects that are closer,” Singer said, referencing the icy bodies found out past Neptune. “They’ve kind of been in this deep freeze, and now they’re just, by chance gravitational interactions, getting kicked back in.”

Scientists know the Centaurs are newcomers to the realm of the giant planets because the region is dangerous territory; an object can rattle around out there for only so long before a planet either collides with it or sends it ricocheting inward or outward — on the scale of 100,000 to 10 million years, a tiny fraction of the solar system’s age.

“Everyone thinks they work on primitive bodies,” Singer said. “But they’re not even close to primitive compared to Kuiper Belt objects, because they’ve had so much stuff happen to them.” Asteroids are the leftovers of planet formation, sure, but some have been through so many collisions that they are merely piles of rubble.

Trojan asteroids, most of which orbit the sun at the same distance as Jupiter, are sometimes dubbed “fossils” of solar system formation — that’s why NASA launched the Lucy mission in October 2021 to fly by a handful of these objects. But while Centaurs and Trojans likely formed in the same frigid place, the Trojans reached Jupiter’s orbit much earlier than the Centaurs left their freezer.

Although scientists hope that Centaurs are pristine, that adjective should by no means imply boring. “They have atmospheres, they have coma kind of like comets in some cases,” Singer said. “There’s the opportunity to have real geology there, too.”

But there’s more. “The really weird thing is that some of them have rings, and we have no idea how these formed basically,” Singer said. “There’s a lot of fun ideas out there, but we don’t have a lot of data to nail down how to form — these would be the first small bodies with rings that would be visited.”

The largest of these objects is called Chariklo. Discovered in 1997, Chariklo is about 190 miles (300 kilometers) across, orbits the sun between Saturn and Uranus and has a ring system. But Chariklo’s orbit means that the object doesn’t spend much time in the main plane of the solar system, so timing a visit is tricky.

“We would love to say we’re going to the biggest one, but the biggest one is not very easy to get to,” Singer said. Instead, the mission is targeting the second-largest Centaur, called Chiron. “Chiron is kind of the sweet spot, because it has a much more agreeable orbit and we can also go to a lot of other objects at the same time as going to Chiron.”

Discovered two decades earlier than Chariklo, Chiron is about 140 miles (220 km) across and also wanders between the orbits of Saturn and Uranus, just with much less of a tilt. Scientists think it has rings and spits material out into space. “We kind of like to describe it as a mini-planet because it has all of this interesting stuff going on,” Singer said.

“It’s not a space potato,” she added. “It’s hard to even guess what the surface might look like, but it would definitely have some interesting geology and in all likelihood things we’ve never seen anywhere else.”

The path to launch

Adding the space telescope to the project has shifted the mission concept from NASA’s smaller planetary science category into the mid-size New Frontiers class, and the mission would build upon the work of a previous New Frontiers mission, New Horizons, which Singer also worked on.

That spacecraft launched in 2006 and flew past Pluto in 2015, providing the first up-close look at the world and revealing phenomena scientists never dreamed of finding there; the spacecraft also flew past a Kuiper Belt object now dubbed Arrokoth in 2019. Uranus’ orbit, the outer range of Chiron’s roaming, is half as far from the sun as Pluto is, slicing the duration of a mission to the Centaur dramatically compared to New Horizons’ flight.

Like New Horizons, the Centaur mission would fly past rather than orbit its targets, gathering as much data as possible during the brief encounter.

But the Centaur mission would also carry reinforcements: tiny cubesats, perhaps as many as 10 of them. On each flyby, scientists would deploy one of these scouts, arranging the cubesat to fly past the Centaur about half a day before or after the main spacecraft does. That’s half a Centaur day, not half an Earth day: With the staggered schedule, the side that the main spacecraft saw at night would be in daylight for the cubesat; stitch the two flybys together, and scientists could map the world’s entire surface.

It’s a technique Singer believes would be feasible at many more destinations than the Centaurs — as long as whatever you want to study spins at least every 20 Earth days or so, the logistics work out, she said.

NASA is next expected to request ideas for New Frontiers missions by 2024. Scientists don’t yet know which solar system bodies will be high priorities for that proposal round; those priorities come from a massive 10-year plan that scientists expect to be published in about a month.

For now, Singer and her colleagues are focused on making the mission concept as strong as possible and championing the idea that cross-disciplinary missions are worth considering, an approach that doesn’t match NASA’s traditional process for selecting missions. “I haven’t seen anything else out there quite like this, but I think it’s mostly just because of the way the funding structure is,” she said.

“The great thing, too, is that we keep discovering more Centaurs,” Singer said. “So this will only get better, fortunately.”

The mission concept is described in a paper published last fall in the journal Planetary and Space Science.

Email Meghan Bartels at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.