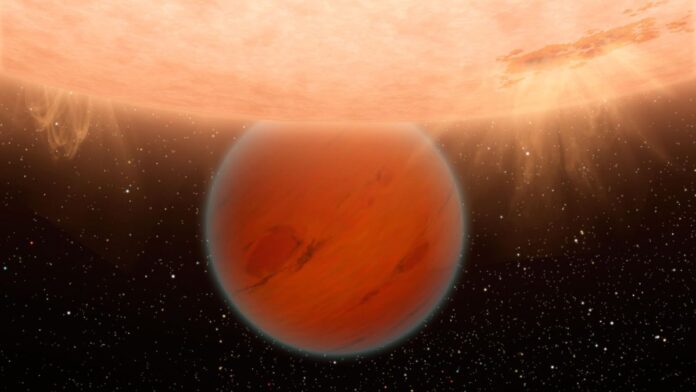

Warm Neptune-size exoplanets are not nearly as common as super-Earths or hot Jupiters — and we are now closer to finding out why.

Our galaxy apparently has a dearth of Neptune-size worlds that orbit close to their host stars — something astronomers term the “hot Neptune desert.” This is a bit of an enigma. Scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS in Switzerland, who are involved in the Desert-Rim Exoplanets Atmosphere and Migration (DREAM) program, investigated the absence of these Neptune-mass exoplanets further by merging two existing techniques.

“Today we have several hypotheses to explain this desert, but nothing is certain yet and the mystery remains,”astronomer and UNIGE assistant professor Vincent Bourrier said in a statement (opens in new tab).

Related: 9 alien planet discoveries that were out of this world in 2022

Researchers have figured out several possible reasons for the hot Neptune desert. Some planets may have originally formed as hot Neptunes, one theory goes, but were so close to their star that the intense radiation obliterated their atmospheres, leaving nothing but a rocky core. It is also possible that hot Neptunes may have migrated farther away from their star after they formed, leaving the desert behind.

In the new study, the researchers used both the radial velocity method and the transit method to study 14 planets in the desert. The transit method detects an exoplanet when it passes in front of, or transits, its star. Radial velocity gives away whether an object is moving toward or away from an observer. The gravitational pull of an orbiting planet makes its star shift slightly in response to where that planet is going, and details of that measured motion can reveal characteristics of the planet, such as its mass.

Bourrier and his team merged these methods to make out a planet’s radial velocity during transit, which gave them an idea of what the orbits of planets in the hot Neptune desert looked like.

Many orbits were determined to be highly eccentric — the less circular the orbit, the more eccentric it is. This was seen as evidence for migration. Three-quarters of the planets studied were found to orbit above their star’s poles, which could be the result of disruptive migration, meaning it is likely these planets were forcefully kicked out of the orbital plane they were born in.

DREAM is a part of the larger SPICE DUNE (SpectroPhotometric Inquiry of Close-in Exoplanets around the Desert to Understand their Nature and Evolution) project, which looks to understand how planets in the desert formed and evolved for there to be so few hot Neptunes in that region.

There are still questions about the Neptune desert whose answers still elude scientists. Until more powerful next-gen telescopes can see more, migration is at least one possibility that could eventually reveal what is behind the absence of hot Neptunes.

The research is described in a paper published online last month in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics (opens in new tab).

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).