Science can be a cold, uncaring partner. Oh, your relationship may start out warm and fuzzy, but while your passion for discovery and truth may endure, science may turn its back on you and say, “find your own path … I’m busy.”

The team members from MIT’s Haystack Observatory that I’ve been sharing the Haughton-Mars Project (HMP) camp with for the past three weeks might need some science couples therapy when they get back to Boston: John Barrett, a scientist and software developer at Haystack; Rigel Cappallo, a postdoctoral research associate there; and Jason Soo Hoo, Haystack’s IT manager and the nominal field Principal Investigator for this deployment. All are working together on the EDGES experiment.

When asked, each of them insists they are merely assisting on Alan E.E. Rogers’ important cosmology project EDGES, a collaboration between Haystack and Arizona State University, but each of them has organically assumed areas of responsibility fully commensurate with their skill sets. EDGES is the Experiment to Detect the Global Epoch of re-ionization Signature (opens in new tab), and, as noted earlier in this series, seeks to validate earlier efforts to measure the re-ionization of hydrogen in the early universe by using passive radio astronomy to listen to some of the earliest radio frequency signals ever. These originated from primordial hydrogen about 150 million years after the Big Bang, the period when the first stars began to form.

Related: A month on ‘Mars’: Trekking through Ingenuity Valley

Rod Pyle is a space historian and author who has created and offered executive leadership and innovation training at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. Rod has received endorsements and recognition from the outgoing Deputy Director of NASA, Johnson Space Center’s Chief Knowledge Officer for his work.

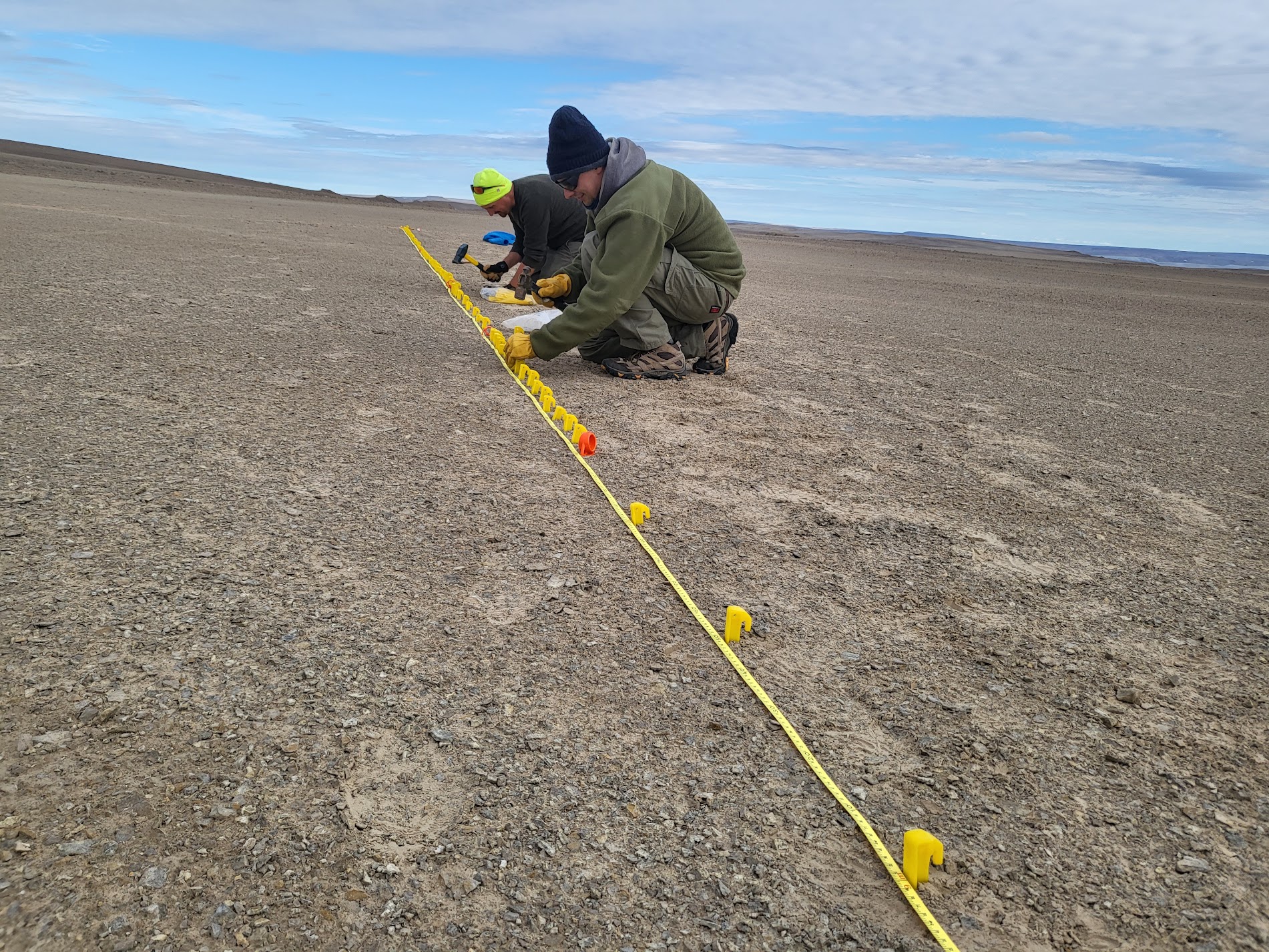

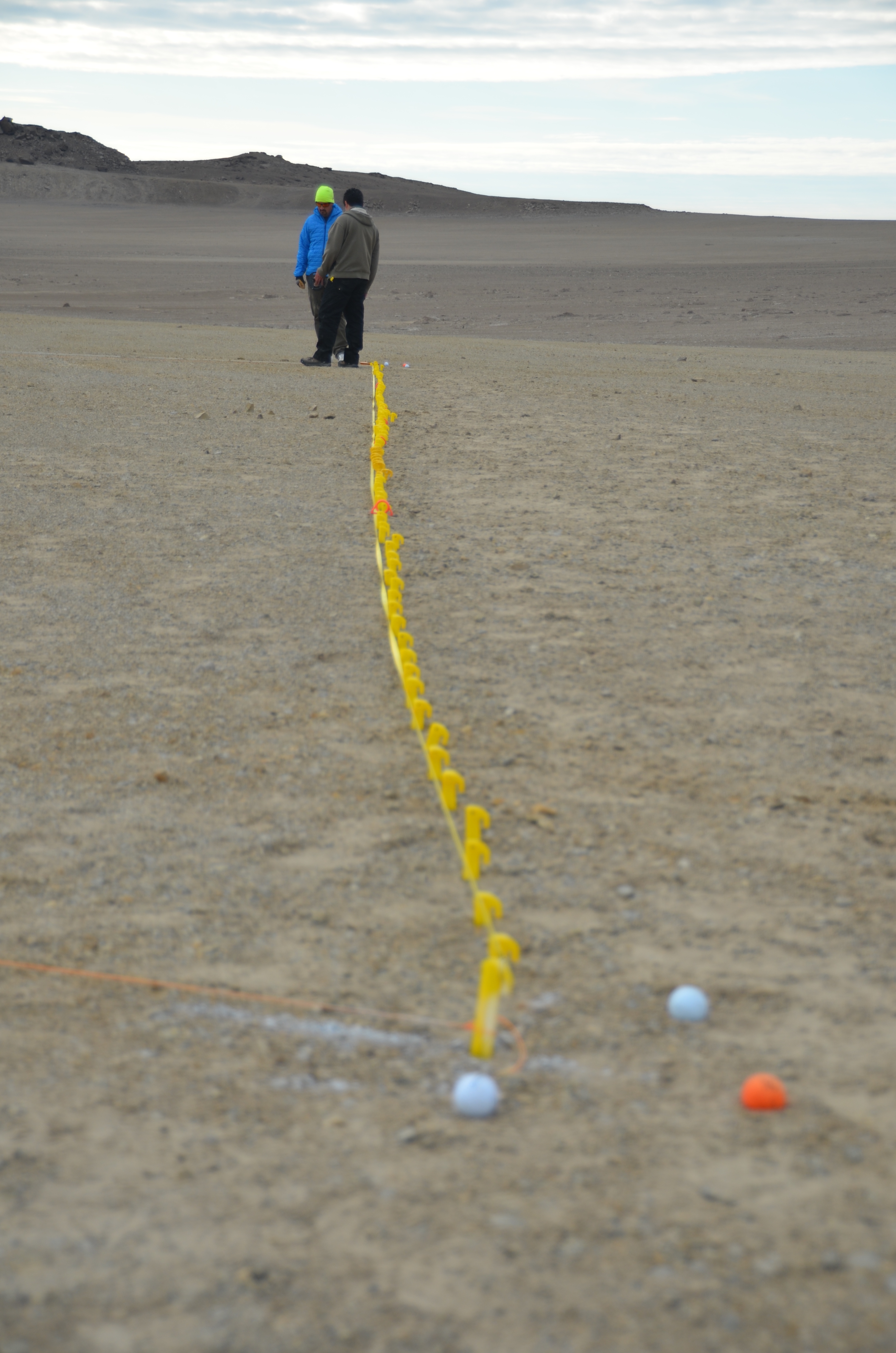

Shortly after arriving at HMP and identifying a nicely flat area not far from the base — yet far enough to not be affected by any radio frequency interference from the base — John, Rigel, and Jason spent a couple of days stretching 5.5 miles (9 kilometers) of wire into a grid pattern — running the wires back-and-forth over a north-oriented rectangle just a few inches apart. Even siting the grid was a challenge — magnetic compasses don’t work properly this close to the pole, so they had to collate multiple GPS readings and eventually built a rudimentary sundial to ascertain true geographic north. This grid, or ground plane, serves to ensure the antenna’s response is smooth in frequency and direction and not affected by any unknown rock structures below the surface.

(opens in new tab)

To accomplish this task, the experiment needed to be placed in an area as close to radio silent as possible, and that’s why they have traveled here, about 15 degrees away from the geographic north pole, where terrestrial radio noise is minimal and where they will be looking away from the radio-noisy center of our Milky Way galaxy. But even here, errant emissions can be found in the FM band, and the team has been working tirelessly to perfect their observations as well as they can.

(opens in new tab)

They arise early to traverse the mile (1.6 kilometers) across rugged terrain to their antenna installation. It doesn’t sound very far, but in biting cold temperatures, with windblown grit in your eyes and mouth, bouncing over uneven, choppy terrain on aging ATVs, it’s anything but fun. And, of course, while one or two of them are working with the EDGES antenna rig, the other must stand guard, scanning in a 360-degree pattern, alert for polar bears that may be prowling — an MIT scientist makes as good a meal as a seal any day. This routine has been repeated every eight hours for weeks, and they have maintained continually sunny spirits throughout these cloudy days.

(opens in new tab)

Early on, John worked tirelessly on the software that drives the antenna and its heating unit, with endless patience. Rigel, who has a mind like a razor and a wit to match, is the other half of the experiment on-site. Jason, who has spent years in the IT world and has traveled to Antarctica in a similar role, supports these efforts.

GET CAUGHT UP WITH A MONTH ON ‘MARS’:

From day one of their work, they have been struggling to identify any radio frequency interference, no matter how small it might be. Ruling out FM radio transmissions from distant stations was the easy part — after those were excluded, the trio walked the HMP base and surrounding areas with a handheld RF meter. There appeared to be a single spike of interference coming from something, but since it never varied from location to location, it was ultimately suggested that this might be a fault in the detector itself.

The first week was spent trying to get the EDGES system to work properly. While earlier versions had been deployed twice before, including in the Australian outback, it had never been tested in these extreme conditions of cold. Because the antenna system is located far from camp, it’s powered by batteries, and at these temperatures, those take the first hit — they are depleted within 8-10 hours. There was also an issue with getting the system’s internal heater to switch on properly —the default settings in the system’s software were not configured properly for the local environment, and tweaks had to be made to the programming.

(opens in new tab)

With software issues ironed out, there was still errant radio noise being detected, and the team has spent the last ten days trying to isolate a possible source. It’s possible that it’s internal to the system — some kind of interference from the circuitry or power source — or that activity from the sun, or its interaction with the Earth’s magnetosphere or ionosphere, may be the issue; we are not far from where the magnetic fields that surround our planet intersect the Earth at its northern magnetic pole. It’s slow going, but they are gathering data 24/7, and Rigel will spend the first few weeks after his return to Boston working to parse the results. With luck they will not only find the culprit with regard to the interference they have detected, but perhaps some usable data from deep space as well.

We won’t know the specific results from this deployment of EDGES for some time, but we do know that a valuable engineering study has been accomplished, that Devon Island appears to be one of the best radio-quiet places in the northern hemisphere, and that this team from Haystack works together under adverse circumstances brilliantly — and that, in the end, may be the most valuable accomplishment of all.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).