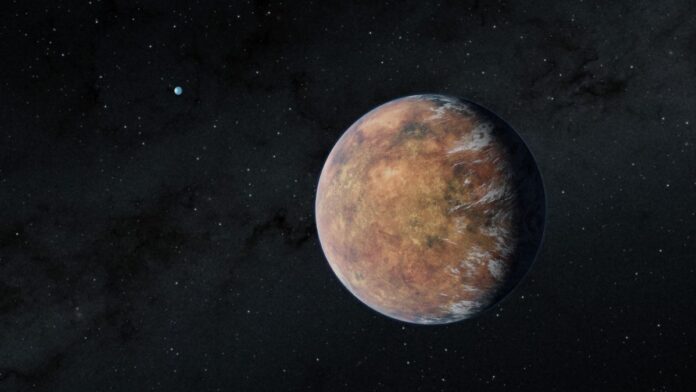

NASA’s leading planet-hunting spacecraft has spotted its second planet that matches Earth’s size and may be able to retain liquid water — and both worlds orbit the same star.

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) launched in April 2018; since then, the mission has discovered 285 confirmed exoplanets and more than 6,000 candidates. One of the most intriguing of the confirmed planets is a world dubbed TOI 700 d, which is about the size of Earth and located in its star’s habitable zone. Now, scientists have determined that the planet has a neighbor that’s just as tantalizing, thanks to an October 2021 alert that the Earth-orbiting telescope had seen something interesting.

“We first started looking at it and we’re like, ‘Is this real?'” Emily Gilbert, an astronomer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, told Space.com. Gilbert and her colleagues are presenting the research at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society, being held this week in Seattle and virtually.

“I was very excited,” Gilbert said. (The timing helped, too: “It was the day before my birthday.”)

Related: 9 alien planet discoveries that were out-of-this-world in 2022

TESS finds planets by staring at stars for a month at a time, looking for small dips in brightness that can indicate a planet passing between the star and the telescope. From these dips, astronomers can estimate the size of the planet and clock its orbit.

In 2020, Gilbert and her colleagues reported the discovery of three planets around a small star called TOI 700 (TOI stands for “TESS Object of Interest”), which is located about 100 light-years away from Earth. That star is a red dwarf, but unlike many of its siblings, TOI 700 is relatively quiet, without the sudden pulses of activity that could fry any life on a nearby world.

“In the full, two-year data set that we have from TESS, we see no evidence of optical flare,” Gilbert said.

Two of the three planets that TESS initially found in the TOI 700 system orbit too close to the star to look much like Earth, but the third world, known as TOI 700 d, is particularly tantalizing. That world, the scientists found, is about 20% larger than Earth and orbits the star every 37 Earth days, putting it in what scientists call the habitable zone, where temperatures should allow liquid water to exist on the surface.

With just those three planets, scientists were already comparing the system to TRAPPIST-1, a system 39.5 light-years away from us that’s known for its seven Earth-size planets. “It’s definitely a really interesting comparison,” Gilbert said. But the TOI 700 system will be easier to continue studying, she noted, given that TRAPPIST-1 is a more active and dimmer star. “The TRAPPIST system is super super compact; all those planets are crammed in really tightly.”

Now, Gilbert and her colleagues say that TOI 700 d has a third sibling, and an intriguing one. This planet, dubbed TOI 700 e, isn’t quite in the region astronomers have typically dubbed the habitable zone, but that definition is in flux. In particular, since astronomers have realized that Venus and Mars likely both once held water on their surfaces, some have proposed an “optimistic” habitable zone, which TOI 700 e resides in.

Gilbert and her colleagues estimate that TOI 700 e is about 95% the size of Earth, so it’s likely rocky and orbits about once every 28 Earth days — putting it in between TOI 700 c and d. The newly discovered world is also likely tidally locked, always showing the same side to its star.

“That’s most of what we know at this time from TESS data alone, but we do have some other campaigns currently underway to characterize this more,” Gilbert said. “No results yet, but exciting things are coming.”

TESS will have its eye back on TOI 700 in just over a week, Gilbert noted, with another nine months or so of data due within the coming year. And the researchers have brought in reinforcements as well. Gilbert is currently observing the system with the Very Large Telescope in Chile, using its Echelle Spectrograph for Rocky Exoplanets and Stable Spectroscopic Observations (ESPRESSO) instrument, which is designed to characterize Earth-like exoplanets. The researchers hope the ESPRESSO observations will allow them to determine the masses of all four planets in the system, and a collaborator is using the Hubble Space Telescope to estimate the star’s ultraviolet emissions — information that could inform climate models for these planets.

Although the James Webb Space Telescope has already proven capable of sniffing out the components of an exoplanetary atmosphere, that skill won’t be used on either TOI 700 d or e, which are each small enough that an atmospheric analysis would take far too long to be practical given the star’s small size, Gilbert said. However, it might be able to study the largest planet, TOI 700 b, she added.

Gilbert said that the new find shows the value of TESS’ extended mission. The spacecraft was originally slated to operate for two years; it began its second mission extension in September 2022, which will continue until October 2024. TOI 700 is located in a patch of the cosmos that TESS sees continually when it is studying the southern sky. All told, Gilbert and her colleagues needed to combine observations of 14 different transits on TOI 700 e to confirm the signal was real.

“If the star was a little closer or the planet a little bigger, we might have been able to spot TOI 700 e in the first year of TESS data,” Ben Hord, a doctoral candidate at the University of Maryland, College Park and a graduate researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, said in a statement. “But the signal was so faint that we needed the additional year of transit observations to identify it.”

Email Meghan Bartels at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.