The first-ever orbital rocket launch from British soil failed on Monday (Jan. 9) in a disappointing setback to the country’s sovereign space ambitions.

Virgin Orbit’s Start Me Up mission launched from Spaceport Cornwall, a civilian airport-turned-launch site located in the southwesternmost point of Great Britain. It’s a relatively modest facility. Temporary portable office blocks accommodated the bustling media crews and the VIP area consisted of a heavy-duty marquee.

Still, the spaceport is fit for purpose. Formerly maintained by the Royal Air Force as a military airport, Spaceport Cornwall’s 9,000-foot (2,740 meters) runway is more than capable of accommodating a Boeing 747-400 passenger airliner – even one that is carrying a roughly 30-ton Virgin Orbit LauncherOne rocket underwing. Despite the fact that Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne rocket encountered an anomaly resulting in launch failure, the mission nonetheless showed that Spaceport Cornwall will create a vital launch capacity for the U.K.’s space ambitions going forward.

Related: Virgin Orbit, UK space agency to investigate rocket launch failure

The modified plane took off without issue, carrying the rocket to an altitude of more than 30,000 feet (9 kilometers). With roughly three quarters of Earth’s atmosphere already below it, the rocket was released and a single Newton Three thruster activated, producing 73,500 pound-force of thrust. Stage separation and second stage firing were also achieved. Shortly afterwards, the rocket malfunctioned and the payload was not delivered to its final orbit. Nine satellites were lost.

“We will work tirelessly to understand the nature of the failure, make corrective actions, and return to orbit as soon as we have completed a full investigation and mission assurance process,” said Dan Hart, Virgin Orbit CEO, in a statement following the failed launch.

Keith Ryden is a professor in space engineering at the University of Surrey in England whose research team helped to develop the Coordinated Ionospheric Reconstruction Cubesat Experiment (CIRCE), designed to monitor solar radiation. The instrument comprised two cubesats that were aboard LauncherOne. Both are now expected to have burnt up in Earth’s atmosphere. “I saw the first stage fire up and it seemed to be going well, and then I went to bed,” he tells Space.com. “Normally once the first stage is fully fired, it usually goes very well after that. So it’s rather odd.”

Ryden says the launch failure is “disappointing” but that work will now begin on a new smallsat instrument designed to monitor high-energy protons in space. “In the end, you’ve got to have a commercially viable future, and that’s all going to depend on reliability. So they [Virgin Orbit] have a lot to prove, but they’ve now put a lot of pressure on themselves to really prove it. It’s not the end of the world, and we would be excited to be part of the next launch in the same way or in a different way.”

Read more: The UK really wants commercial spaceports

The U.K. as a space underdog

The excitement at the press conference the day prior to launch was palpable – enough to offset the January winds and rain whipping the coast from the Atlantic. Melissa Thorpe, head of Spaceport Cornwall, joined the facility upon its inception in 2014. She told Space.com that the past nine years of her work had “always been [aiming] towards that first launch.”

“It’s something you don’t see every day in somewhere like Cornwall, and it’s a bit of an underdog story as well,” Thorpe said at the press conference the day prior to the launch. “I think people love an underdog story, especially in the U.K.”

The United Kingdom has historically held a prominent place in the realm of science and research, spending £38.5 billion – around 1.74 percent of GDP – on research and development in 2019. And despite leaving the European Union in 2020, the country committed around 2 billion Euros to the European Space Agency over the five years between 2020 to 2024.

Satellite manufacturing has traditionally been the country’s forte as far as space is concerned. At the Sunday (Jan. 8) press conference, Ian Annett, deputy chief executive of the U.K. Space Agency, said the U.K. builds more satellites than anywhere else outside of the US.

“The U.K. has pioneered the microsatellites which are suitable for launching from Cornwall,” Ryden said. “This revolution started in 1981 when Professor Sir Martin Sweeting developed the University of Surrey Satellite or ‘UoSAT-1’ and launched it on a U.S. rocket. It was only 70 kg, which was very small for its day. This and subsequent missions proved that small, low-cost but high-capability satellites were feasible.”

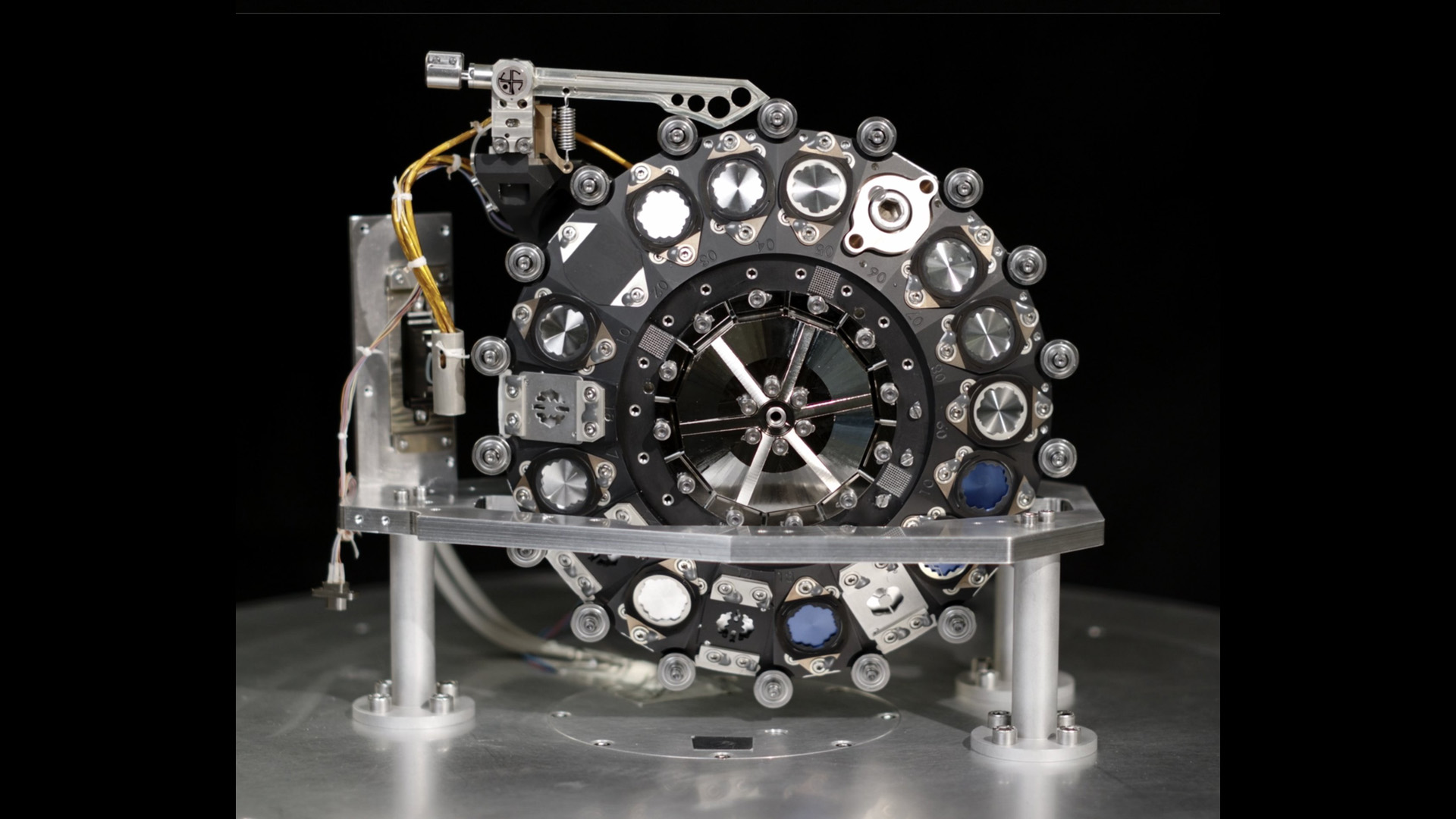

One of the country’s most recent space engineering achievements was leading the European Consortium in building the Mid-Infrared Instrument, or MIRI, aboard the James Webb Space Telescope – an instrument that allows the telescope to see the redshifted light of distant astronomical objects.

In other ways though, the country’s footprint in space has been small compared to that of its European neighbors. Today there is one active British astronaut – Timothy Peake – but of the 18 former members of the ESA astronaut corps, none have been British.

The U.K. has also never had sovereign launch capacity. The closest the country came to achieving this was in 1971, when it launched one of its 43-foot-tall (13 meters) three-stage Black Arrow rockets into space from Australian soil, placing a research satellite into low-Earth orbit. Despite this successful launch, the project was canceled by the U.K. government on economic grounds that same year.

“Alas, Black Arrow was canceled immediately after its first [orbital] launch due to cash limitations and launch leadership was handed to France who went on to develop the successful Ariane rockets,” says Ryden.

Read more: A solar power plant in space? The UK wants to build one by 2035

A missed opportunity

The launch of Virgin Orbit’s Start Me Up Mission from Spaceport Cornwall could have been a milestone in a new era of British space capability at a time of heightened interest in small, privately-owned satellites – the ideal payload for Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne vehicle.

“We’ve seen the low Earth orbit economy grow rapidly over the last few years alone,” Ian Annett, deputy chief executive of the U.K. Space Agency, told Space.com. “So there’s definitely a demand signal for the launch of small satellites into space. The global space economy is worth well over $360 billion dollars, and the launch economy within that is about $20 billion. We can see ourselves here within the U.K. as being able to sit on some of that market.”

Having sovereign launch capability is also beneficial in terms of skills it brings to the country, added Annett, not least through inspiring young people to get involved in STEM fields. “We want to make sure that we continue to develop our nation so that people have those kinds of skills, and who can then continue to work either in the space industry or other technical industries in the U.K. and make sure that we become a nation that builds things and does great engineering projects again.”

Today and in the past, the U.K. and U.K.-based companies have had to ship payloads overseas in order to take part in space missions, relying on ESA and its Ariane and Vega rockets, NASA and SpaceX in the U.S., and, formerly, Russia’s Roscosmos space agency.

“That’s just not particularly great to do, and not particularly cost-effective,” Matthew Archer, Commercial Space Director at the U.K. Space Agency, tells Space.com.

Looking ahead

The message from the U.K. Space Agency in the hours following the mission’s failure is that this is not a death knell for orbital launches from the U.K. While it is not clear when or if the Start Me Up mission might be re-attempted, Thorpe told Space.com ahead of Monday’s mission that Spaceport Cornwall was “definitely keen” to host another Virgin Orbit launch later in 2023. There are also other launch providers working with them.

“We’ve announced a memorandum of understanding with Sierra Space, and that’s Dreamchaser,” Thorpe said. “Dreamchaser will take off vertically in the U.S., but it needs a runway to land on and a licensed spaceport to come back to. So they’ll go up to, say, the International Space Station, pick up experiments or even humans from it, and bring them back down. And we will be the landing site for that. And then we’ll hopefully be announcing another operator in the coming months as well.”

According to Archer, Start Me Up, despite failing this week, succeeded in creating horizontal launch capacity for the U.K. – Spaceport Cornwall still has the U.K.’s first ever spaceport license, granted to it by the Civil Aviation Authority in November last year – and there are plans for vertical launches from the U.K.’s northern reaches in Scotland.

The U.K.’s geography is an important factor. “[We’ve] obviously got access over the Atlantic, so if you want to go south and access a retrograde orbit, that’s really important,” said Archer. “But equally, polar orbits are really valuable for two high-growth industries: Observation and telecommunications. They love having polar orbits because you get regular flypast over areas that aren’t always covered by other systems.”

For now, UKSA says it will work with Virgin Orbit as it investigates the orbital insertion failure in the coming days and weeks.

Ed Browne is a freelance journalist based in the U.K.. Formerly a science reporter for Newsweek, he has a Bachelor’s in journalism in addition to a diploma in multimedia journalism from the National Council for the Training of Journalists.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).