Now we can factor erosion on the Red Planet into our search for life on Mars.

A new study attempts to find periods of more intense erosion on Mars in hopes of understanding when water flowed on the world’s surface. Water can carry larger pieces of rock into collisions, breaking the rocks faster, so accelerated erosion might be a signal of watery, and in turn potentially habitable, conditions.

As rock eroded, the resulting dust blew into craters and settled down, providing a potential measurement point to assess erosion on Mars, according to the researchers.

Related: A brief history of Mars missions

The study probed the different types of rocks available on Mars and possible erosion rates. The planet is mainly covered with a fine layer of talcum-like dust, with elements including sodium, potassium, chloride and magnesium. Below the dust is a crust that is mostly made up of volcanic basalt rock, while a largely dormant mantle beneath contains silicon, oxygen, iron, and magnesium.

“Our study determines the timing and rates of sediment erosion and accumulation over Mars’ geologic history in a completely novel way, and for the first time quantifies a measure of the erodibility of each of the types of rocks we see on Mars’ surface,” lead author Andrew Gunn, a lecturer in the Monash University school of Earth, atmosphere and environment, said in a university statement (opens in new tab).

“We show that the abundance of sands blown by wind into craters on Mars’ surface can be linked to the climate history of the planet, unlocking a new way to understand when in geologic time Mars may have been habitable,” Gunn added.

One common proxy for assessing erosion rates is to use “crater counting”, or estimating the number of craters on the surface and then assessing their age by how eroded they are. The complication, however, is that rates of erosion may change over time.

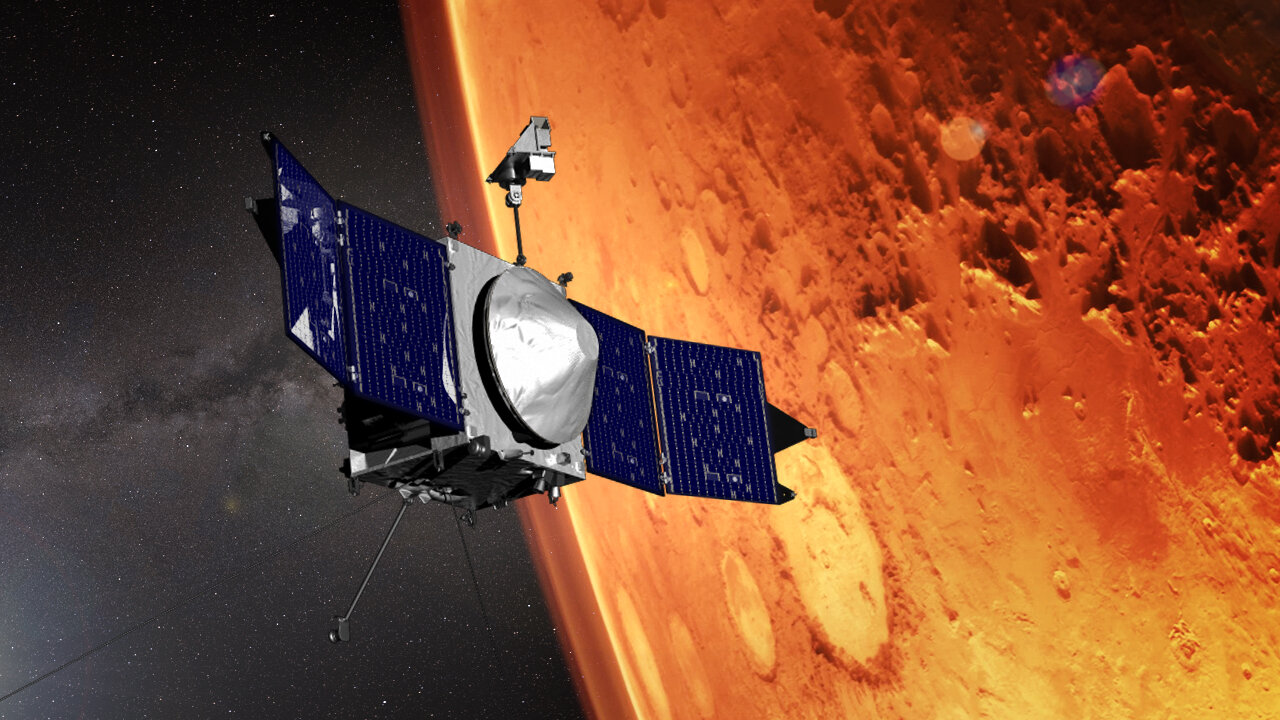

The new study used several datasets, including information from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) that ran aboard the NASA Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) spacecraft that operated at the planet between 1997 and 2006. Scientists also gathered geology maps and climate simulations.

The aim was to estimate erosion through plotting the sedimentary cycle on Mars. Earth’s plate tectonics “recycle” the surface, meaning that sediments are often buried over time. Mars, however, has no tectonics and should have a record of accumulations from ancient times to the present day.

Erosion tends to accelerate, the researchers noted, as rocks collide in liquid conditions. This collision process would then produce sediment, but the sediment often needs to be broken down by water before it is light enough for the wind to pick the dust up.

The implication is there was running water involved in the process, the study suggests. “Seeing high rates of accumulation in a certain period of Mars’ history indicates that it was much more likely there was active rivers eroding material then,” Gunn said.

A study based on the research was published (opens in new tab) in the journal Geology on May 12.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.