Our planet is under constant attack.

Every day, Earth is bombarded with about 48.5 tons (44 tonnes) of space rocks, dirt, and debris, according to NASA (opens in new tab). Fortunately for us, the vast majority of it completely disintegrates in our atmosphere. But occasionally some pieces slip through and reach the surface of our planet, officially becoming meteorites.

Scientists have long wondered exactly how meteorites survive the fiery entry through the atmosphere, during which meteors heat up to some 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1649 degrees Celsius). But a new study sheds some light on the mysterious process, indicating that the largest meteorites come from an asteroid’s backside, which is the last part of the asteroid to break up during atmospheric entry.

Related: What Are Meteorites?

Meteor astronomer Peter Jenniskens of the SETI Institute and NASA Ames Research Center led a study on asteroid 2008 TC3, a six-meter rock that entered the atmosphere in 2008. Given its size, astronomers spotted the asteroid some 20 hours before it disintegrated, allowing them to measure its size and shape, as well as track its exact trajectory — many meteors are surprises, so the acquisition of this kind of data is rare.

After it exploded in the atmosphere, meteorites rained down across the Nubian Desert in Sudan across an area some 4.3 by 18.6 miles (7 by 30 kilometers) in size. Jenniskens organized the recovery and cataloging of the meteorites with University of Khartoum professor Muawia Shaddad and his students. They found more than 600 meteorites from the size of a thumbnail to the size of a fist.

Related: Shape of Small Asteroid that Hit Earth Revealed

The smaller fragments were spread across a long, narrow area within the debris field that matched the trajectory of the asteroid, while the larger fragments deviated more widely from the asteroid’s path. These findings were a surprise to the team.

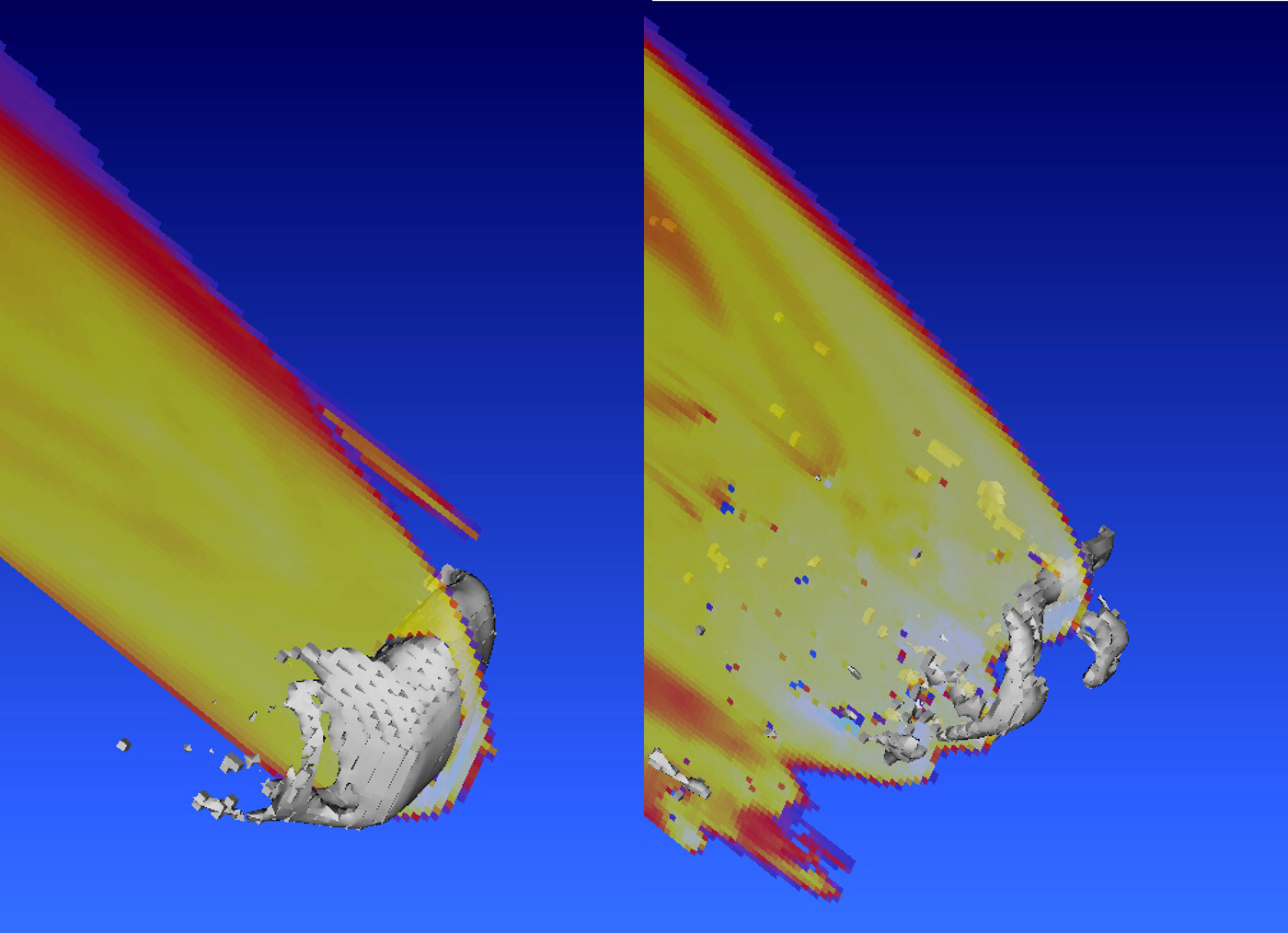

Using available data on the size, shape, and trajectory of asteroid 2008 TC3, theoretical astronomer Darrel Robertson of NASA’s Asteroid Threat Assessment Project (ATAP) at NASA Ames Research Center created a computer model to simulate the asteroid’s breakup.

“The asteroid melted more and more at the front until the surviving part at the back and bottom-back of the asteroid reached a point where it suddenly collapsed and broke into many pieces,” Robertson said in a statement (opens in new tab). “The bottom-back surviving as long as it did was because of the shape of the asteroid.”

Robertson’s model shows that the smaller fragments broke off earlier during atmospheric entry and fell nearly directly downwards. But the larger ones originated from that bottom-back section — when it exploded, it sent the large fragments in a variety of directions, accounting for their spread in the debris field.

“Most of our meteorites fall from rocks the size of grapefruits to small cars,” said Jennisken. “Rocks that big do not spin fast enough to spread the heat during the brief meteor phase, and we now have evidence that the backside survives to the ground.”

The team’s research was published in the journal Meteoritics and Planetary Science (opens in new tab) on Aug. 8.

Follow Stefanie Waldek on Twitter @StefanieWaldek (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).