Up until now, the planet that has been dominating our morning sky has been brilliant Venus, which is visible low in the east-northeast sky beginning literally at the crack of dawn – about 90 minutes before sunrise.

But before Venus rises, it is Jupiter that dominates the sky from late evening onward, outshining everything in the heavens but the moon.

This week the king of the planets rises around 9:45 p.m. local daylight time and — speaking of the moon — late on Sunday (Aug. 14) if you’re facing east soon after 10:30 p.m., you’ll see a waning gibbous moon, three days past full, standing a little over 5 degrees to the right of Jupiter.

Your clenched fist held at arm’s length measures roughly 10 degrees in width, so on Sunday night, just over “half a fist” will separate Jupiter from the moon.

Related: Jupiter: A guide to the largest planet in the solar system

Jupiter and the moon will remain visible right on through the rest of the night, peaking toward the south just before 4 a.m., at an altitude that measures more than halfway from the horizon to the point directly overhead (the zenith).

Moreover, the orientation before the two will have changed noticeably; as they cross the southern meridian at that early hour, Jupiter will appear to be glowing directly above the moon. And they will also appear to be closer to each other with the gap between the two having shrunk to 3 degrees.

Opposition, when it will be nearest to Earth and in the sky all night long — from sunset to sunrise — is just a little over six weeks away, on Sep. 26th. Also on Sunday, Saturn will arrive at its own opposition. It’s located 46 degrees to the west (right) of Jupiter. Since your clenched fist held at arm’s length is roughly 10 degrees in width, Saturn and Jupiter are currently about 4.5 “fists” apart.

Dance of the moons

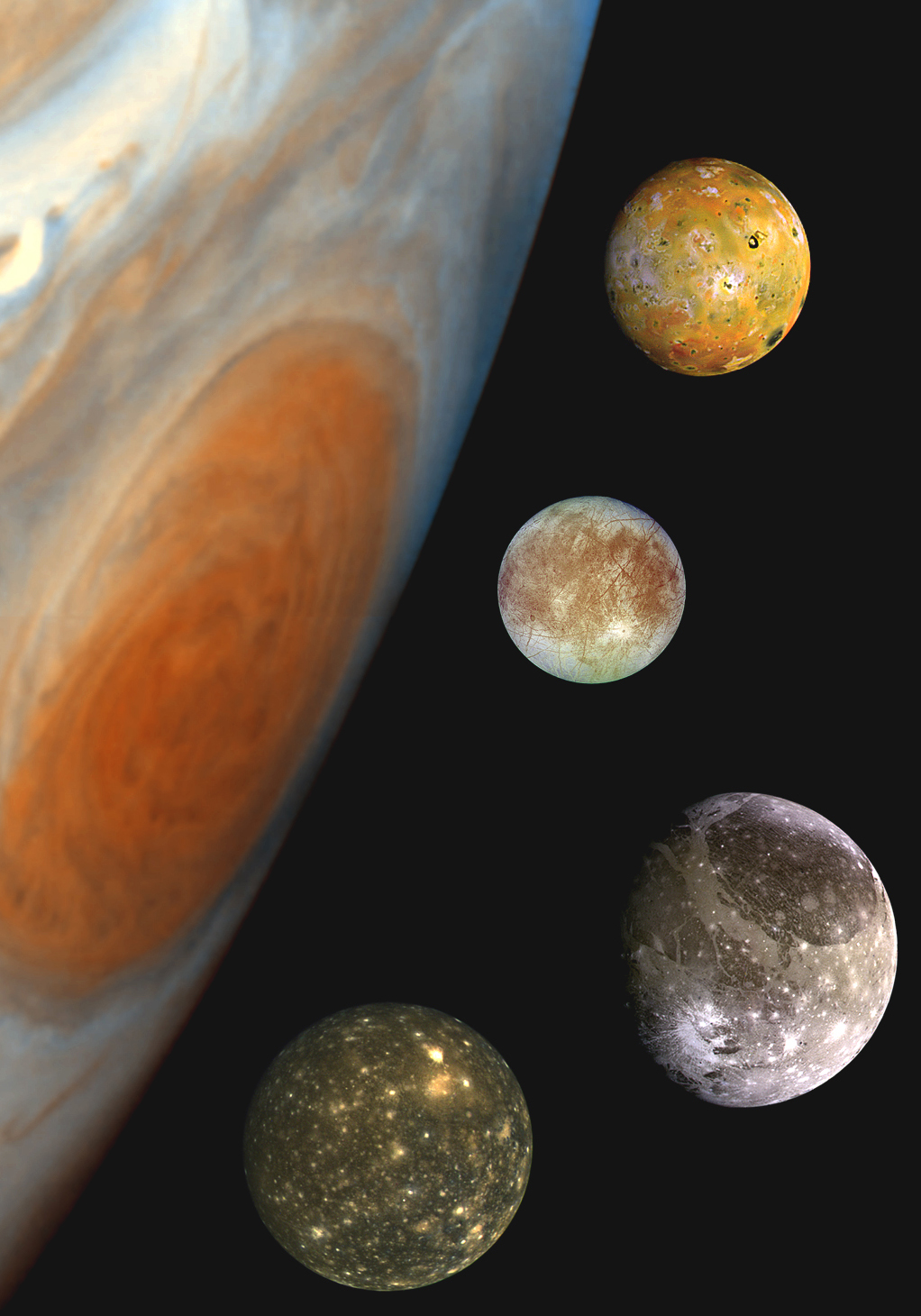

And don’t forget Jupiter’s four major moons, which were discovered 412 years ago by Galileo. They serve as a constant delight to amateur astronomers and can be seen in any telescope and even binoculars. They orbit Jupiter so quickly (1.68 days for Io to 16.7 days for Callisto) that they change their appearance from hour to hour and night to night.

As an example, if you train a telescope on Jupiter on Sunday night, initially, you’ll see a single moon (Io) on one side of Jupiter and two (Ganymede and Callisto) on the other. But at 11:28 p.m. EDT (0328 GMT Monday, Aug. 15), the fourth moon (Europa) will emerge into view from behind the disk of Jupiter, joining Ganymede and Callisto.

Then on Monday at 2:15 a.m. EDT (0615 GMT), Io will fade away as it becomes eclipsed by Jupiter’s shadow. Shortly thereafter Io will pass behind Jupiter, but will emerge back into view a little over three hours later. Those in the central and western states, where the sky will still be dark, will then be able to see all four moons aligned on one side of Jupiter.

Size (and Distance) Matters

Finally, when you look at the moon and Jupiter late on Sunday night, try to become aware of the difference in both their respective sizes and distances.

The moon, of course, far outshines Jupiter by more than 9 magnitudes; a brightness ratio of 4,370 to 1.

But the moon is also much smaller than Jupiter. Indeed, the diameter of our natural satellite measures 2,158 miles (3,474 km) compared to Jupiter’s 88,846 miles (142,984 km) width.

What makes the moon loom so much larger and brighter is its distance. On Sunday night the moon will be 232,300 miles (373,600 km) from Earth. But Jupiter will be 1,681 times more distant: 390.6 million miles (628.5 million km) away.

And the fact that the moon is so much closer to us compared to Jupiter, means it moves much more rapidly in the sky compared to the big planet, at a rate of roughly its own apparent diameter per hour. So, that’s why when they ascend the predawn southern sky, the moon will appear noticeably closer to Jupiter compared to when they were rising in the east several hours earlier.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium (opens in new tab). He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine (opens in new tab), the Farmers’ Almanac (opens in new tab) and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).