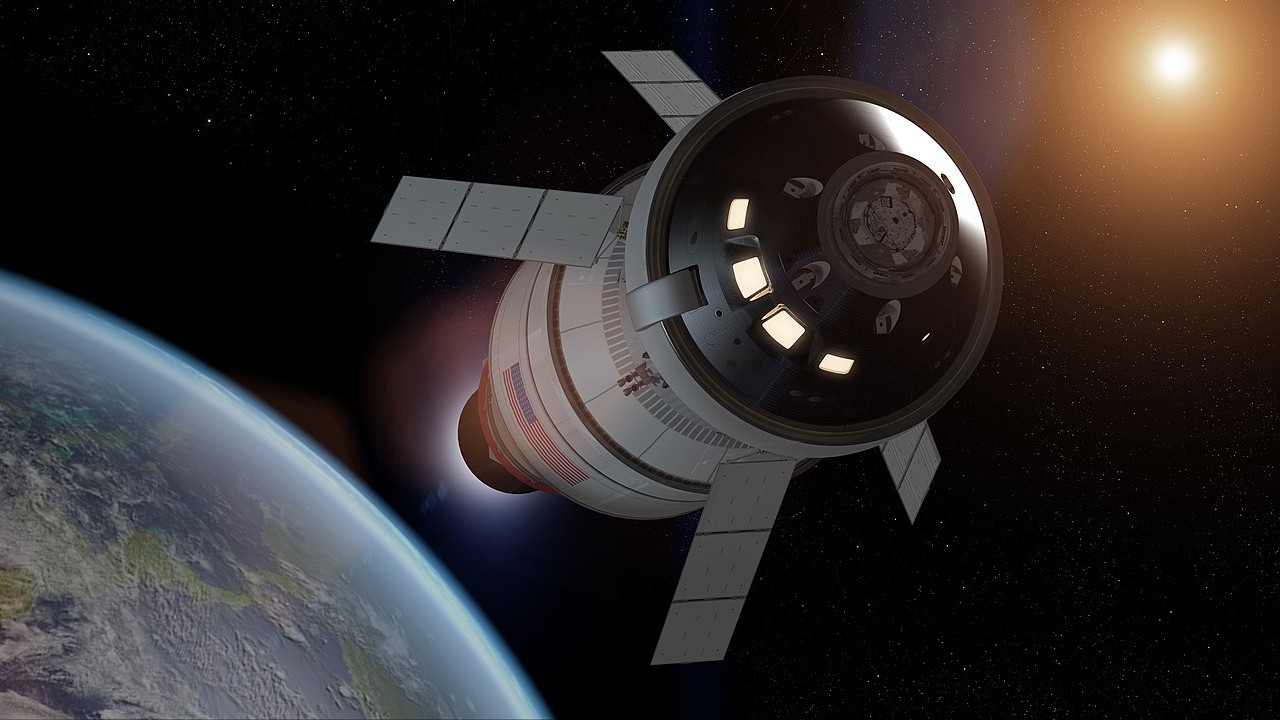

NASA’s first crewed landing of the Artemis program will see boots on the moon no earlier now than 2026, the agency’s inspector general said.

NASA Inspector General Paul Martin delivered the news to lawmakers during a House Space and Aeronautics Subcommittee hearing on Tuesday (March 1) as part of a larger update on the Artemis program, which is facing delays to its first mission as well.

“Given the time needed to develop and test the human landing system and NASA’s next generation spacesuits, we estimate the date for a crewed lunar landing likely will slip to 2026 at the earliest,” Martin said during his livestreamed opening remarks.

Related: NASA’s Artemis 1 moon mission explained in photos

Live Updates: NASA’s latest Artemis 1 moon mission in action

These items have been tricky points for Artemis for several months, along with its ballooning cost. The first four Artemis missions are expected to cost $4.1 billion each according to a November 2021 audit by the NASA Office of Inspector General.

The lags and extra budget are partly due to technical issues, and partly due to protests and a lawsuit by Blue Origin last year (all resolved by November) concerning NASA’s sole-source award of the HLS contract to SpaceX’s Starship system.

Martin’s news came just days after NASA announced that Artemis 1, an uncrewed flight around the moon, would launch no earlier than May, but even that timeline is in doubt due to the amount of data analysis and other work to perform on key tests, the agency indicated last week.

During questioning, Martin acknowledged the role of the inspector general is to be more critical of timelines than NASA, but said that the 2025 deadline the agency is aiming for doesn’t appear to be feasible. (That deadline is itself an extension of the Trump-era 2024 landing that was abandoned in November.)

Martin said there are challenges that need to be faced, “not the least of which would be getting the human landing system certified to operate spacesuits,” along with changes in the agency’s acquisition strategy that is expected to take more time in procuring key technologies “that are not mature.”

These factors, he said, “often point to taking longer and [requiring] development to get there. So 2025 is is not impossible, but it seems improbable.”

The U.S. Government Accountability Office indicated similar pessimism with the 2025 aim to put people on the moon again, in NASA’s first effort since 1972 at a crewed moon landing.

Testimony from William Russell, the GAO’s director of contracting and national security acquisitions, indicated the problem is that NASA is seeking to manage “multiple risks simultaneously” while achieving a tight deadline.

Russell pointed to factors such as the seven-month delay induced by the HLS disputes, a key change in spacesuit development to pivot the work to a contractor instead of in-house work, and cost growth for the Space Launch System rocket and other key infrastructure required to support a human landing.

“We found that NASA had not yet finalized roles, responsibilities and authority for Artemis, and NASA is currently in the process of reorganizing the Human Exploration Mission Directorate,” Russell said of a portion of the GAO’s recent set of reports on Artemis.

“It’s too early to tell the outcome of this effort,” he added of the organization. “Given the scale and complexity of programs, it will also be important that NASA continue to hold integration with us going forward, to reconcile changes across the program.”

NASA, for its part, pointed to unanticipated issues that contributed to cost growth and schedule delays, particularly involving the coronavirus pandemic, which has created supply chain hiccups and personnel challenges due to safety protocols.

“Every bit of work that I’ve mentioned is possible because of the people of NASA and our private sector partners,” James Free, the agency’s associate administrator of the exploration systems development mission directorate, said of the work so far undertaken on Artemis 1.

“Our people have delivered despite COVID, which includes losing some of our teammates because of the virus,” he continued. “They’ve come to work while their homes were damaged, and without power due to severe storms. They’ve come with the spirit of exploration that has and always will be as tangible as the hardware.”

Free did not speak directly about timelines for the Artemis 3 crew landing, but said more information on costs and timelines will be forthcoming as NASA formulates its next budget. He emphasized his approach, however, is to keep “a realistic schedule and budget.”

Speaking of the reorganization of his directorate, Free noted the reasoning was to deal with a greater scope of programs due to the addition of Artemis. The work was done to have his organization work on the development, and then to hand off the operations to NASA’s operations mission directorate once the technology is mature.

For long-term planning, another key goal of the reorganization is to allow Free’s directorate to mature technology for what he says is the ultimate goal of Artemis: to put two people on the surface of Mars for 30 days and safely return them to Earth.

Working on the moon would allow the agency to learn about astronaut behavior in a similar partial gravity environment, although NASA acknowledged the lander would have to be reconfigured to work in a Martian atmosphere.

Such a Red Planet mission, though, is in such an early stage that Martin, speaking on behalf of NASA’s Office of the Inspector General, said he hasn’t received a reliable estimate yet on cost.

“Mr. Free indicated rebuilding NASA’s building capabilities, many of which they hope to use on an eventual Mars mission,” Martin said. “So we will continue as an Office of Inspector General to look at both what they’re spending now, and how they’re developing the equipment and the missions for the future.”

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.