Russia is ready to reactivate its moon exploration agenda, a former Soviet Union enterprise that ended decades ago. The last in the series of pioneering Soviet robotic lunar missions was Luna 24, which sent about 6 ounces (170 grams) of moon material back to Earth in 1976.

Russia’s planned Luna 25 mission is set to kick-start a sequence of lunar outings that also involves Europe and China. For example, Russia intends to collaborate with China on the International Lunar Research Station, which is targeted to be operational by 2035.

Russia’s rekindling of its lunar exploration objectives would clearly be bolstered by the success of Luna 25, a lander mission scheduled to launch this July.

But how Russia and China’s moon exploration plans will truly jell, and how this partnership might influence NASA’s lunar “rebooting” via its Artemis program, are not clear.

Related: The top 10 Soviet and Russian space missions

Primary destination

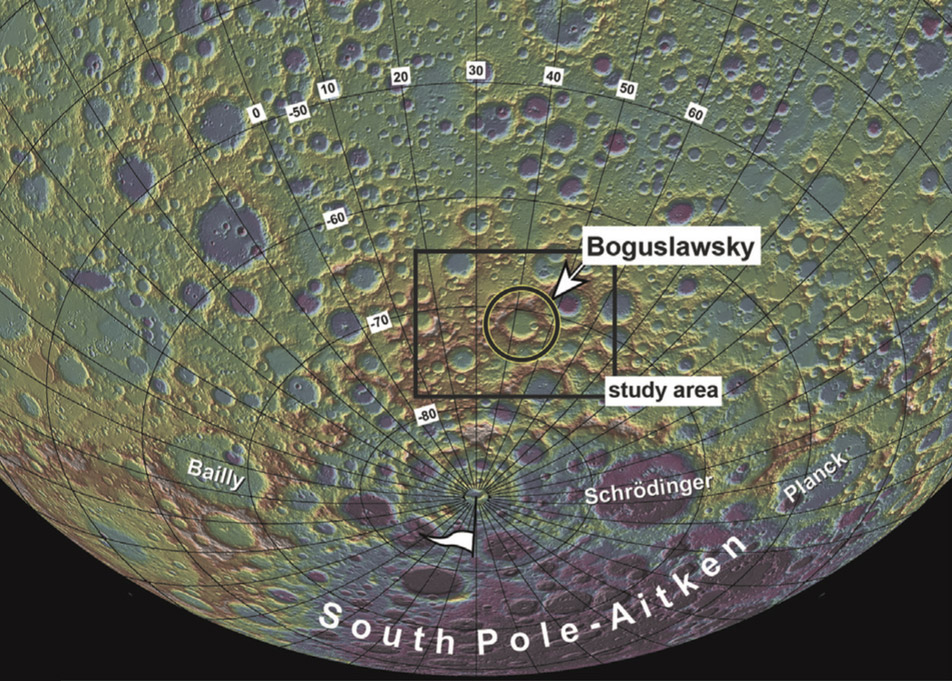

Luna 25 will launch atop a Soyuz-2.1b rocket with a Fregat upper stage from the Vostochny spaceport in the Russian Far East. The probe’s primary destination is the moon’s south polar region — specifically, a spot north of Boguslavsky Crater. (An area southwest of Manzini Crater is a backup locale).

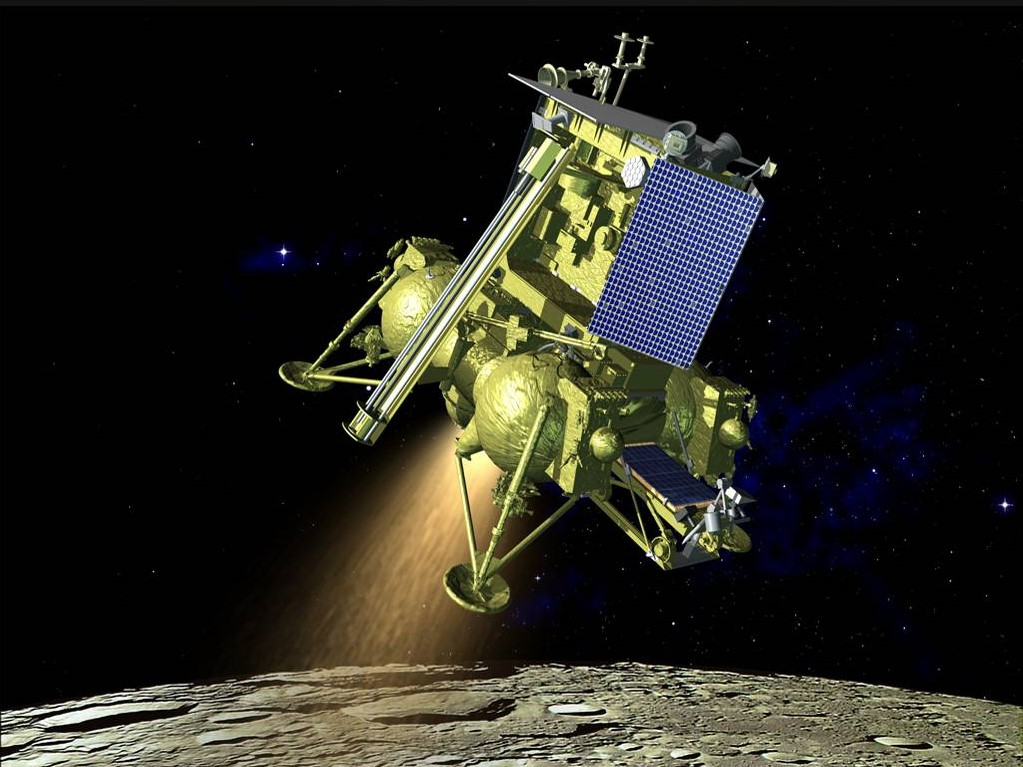

Russia’s NPO Lavochkin, a spacecraft building firm, constructed the lander, which is billed as a pathfinder probe for testing soft-touchdown technologies in the moon’s circumpolar region and conducting contact studies of the lunar south pole.

Pavel Kazmerchuk, Luna 25 chief designer at Lavochkin, has stated that all scientific instruments have been installed on the probe. Electro-radio engineering testing is currently underway, to be completed in March. Development of onboard software for the craft is scheduled to be finished in April.

But Luna 25’s road to the moon hasn’t been an easy trek. Problems found during testing of the nearly 2-ton spacecraft spurred slips from an October 2021 liftoff to May 2022, and now the craft is being readied for a “preferred” July 23 departure.

“In 2021, the Luna 25 spacecraft has been fully assembled; a large amount of ground experimental testing has been performed. The spacecraft is to be launched from the Vostochny Cosmodrome within the launch window of May 25 to October 19, 2022, but we are aiming at July,” Dmitry Rogozin, director general of Roscosmos, Russia’s federal space agency, said in a statement last month.

Related: Every mission to the moon in space history

Main tasks

Luna 25 is designed to operate on the surface of the moon for at least one year, making use of a suite of sensors to study the lunar topside and dust and particles in the moon’s wisp-thin atmosphere, or exosphere.

According to Lavochkin, Luna 25 has three main tasks: develop soft-landing technology; study the internal structure and exploration of natural resources, including water, in the circumpolar region of the moon; and investigate the effects of cosmic rays and electromagnetic radiation on the surface of the moon.

The lander carries eight Russian instruments, including a robotic arm to scoop up lunar regolith, and one developed by the European Space Agency (ESA) — a camera called Pilot-D, a demonstrator terrain relative navigation system.

Talent and experience

Eagerly awaiting the Luna 25 mission is James Head, a geoscientist in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences at Brown University in Rhode Island.

“It is really great to anticipate the launch, landing and operations of Luna 25 in the south polar region of the moon later this year, and see Russian scientists and engineers bring their huge array of talent and experience into the active arena of lunar exploration,” Head told Space.com.

“It will be many years before other countries will be able to duplicate the decades of groundbreaking robotic lunar exploration accomplished by our Russian colleagues over 40 years ago, with robotic lunar rovers and three sample-return missions,” Head said.

Follow-on missions

According to ESA, the Luna 26 orbiter is scheduled to launch two years after Luna 25. Luna 26 will perform remote scientific measurements and serve as a possible communications relay for the next lander mission. It will transmit data back to ground stations on Earth, including ESA’s ground station network.

The Luna 27 lander will launch one year after Luna 26 and will be larger than its predecessor, Luna 25. It will fly to a challenging landing site closer to the lunar south pole using the European Pilot technology as its main navigation system. Luna 27 will deploy the ESA-provided Prospect drill that will search for water ice and other compounds under the lunar terrain.

Currently, NPO Lavochkin is blueprinting a Luna 28 project for the delivery of lunar soil from the south polar region, an effort that is also designed to further subsequent expeditions to deploy a lunar base.

Related: How living on the moon could challenge colonists (infographic)

Roadmap for the moon

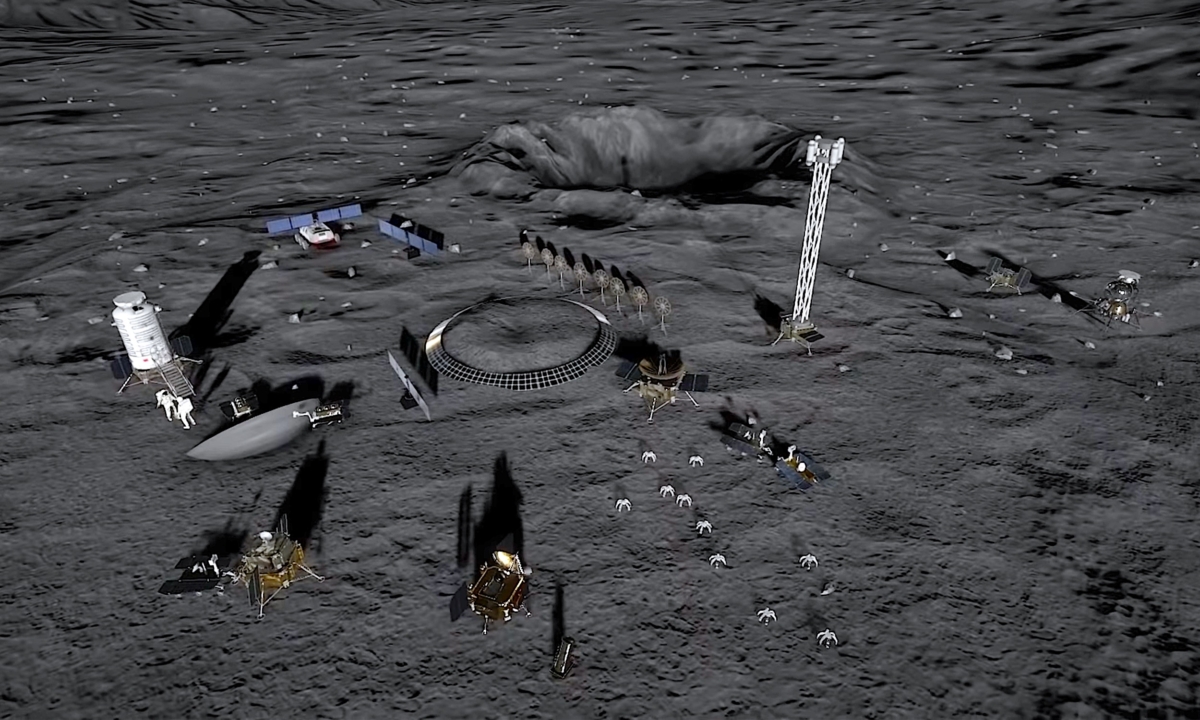

Last year, Rogozin and Zhang Kejian, the chief of the Chinese National Space Administration (CNSA), signed a memorandum of cooperation to begin orchestrating an International Scientific Lunar Station.

An early roadmap for the moon outpost calls for a complex of experimental research facilities — on the lunar surface and/or in lunar orbit — to conduct tasks that make possible a long-term human presence on the moon.

China launched the research station project together with Russia, also initiating the Sino-Russian Joint Data Center for Lunar and Deep-space Exploration. China is working with Russia to coordinate its 2024 Chang’e 7 lunar polar exploration mission with Russia’s Luna 26 orbiter mission.

Competitive game?

It’s good news that the moon is getting more attention, said Clive Neal, professor in the Department of Civil Engineering & Geological Sciences at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

Like Head, Neal is an authority on lunar science and exploration. Neal sees encouraging signs that a robust economy will develop in Earth-moon space — an economy that could be a template for doing similar things elsewhere in the solar system. But he also raised a number of concerns.

“The trouble we’ve got when looking at Russia and China — it appears to be a competitive game that is being played,” Neal told Space.com. “I hope this is going to be a cooperative effort rather than something competitive in nature.”

That said, Neal would like to see definitive plans flowing from NASA regarding a moon station. The American agency has stated that it aims to build a research outpost on the moon via its Artemis program, but details remain scarce at the moment.

“NASA needs to get serious about its base camp plans, because I don’t think it is right now,” Neal said. “There’s a lot of bluster about sustained human presence on the moon, but what does that mean? It doesn’t mean permanent.”

Get serious about the moon

Neal said that he is “cautiously optimistic” that 2022 will be a great year for lunar exploration. Part of the optimism stems from the plans of American companies to deliver science and technology to the lunar surface through NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services initiative.

“They are now cutting metal. They’ve got payloads. They’ve got contracts. And they’ve got to deliver,” Neal said. “I hope NASA will seize this opportunity as something to build into bigger and better things.”

But Neal added that the U.S. space agency “needs to get serious about the moon … and Congress needs to provide the funding for NASA to get serious.”

Lacking today is a resource prospecting campaign, one that is international in character, Neal said. “If you don’t do the grunt work and the prospecting, you are never going to know if lunar resources can be utilized to do what some say they are going to be used to do.”

Moon-exploration planners also need to define and implement a resource-prospecting campaign, Neal added. It remains unknown how such a campaign will operate and who will coordinate it.

“If NASA had an Artemis program office, perhaps that would be a good place for it. I’m hoping you’re getting my sense of frustration,” Neal said.

Neal said that he wishes good luck to China, Russia, NASA and all the American commercial groups in their moon endeavors. “If we all banded together to do this for the good of all humankind, then I think we’d be in good shape,” he concluded.

Leonard David is author of “Moon Rush: The New Space Race” (National Geographic, 2019). A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.