Based on the latest national forecast, skies will be mainly clear on Monday (July 4) evening across a large part of the contiguous United States (the “Lower 48”), as millions gaze skyward to be entertained by pyrotechnics displays in celebration of the 246th year of American Independence. The only exceptions might be across parts of the Pacific Northwest where cloud-filled skies may prevail along with a slight chance of spotty light precipitation; parts of New Mexico and Colorado where showers and thunderstorms could fall, and portions of the Piedmont and Southeast US that might also be plagued by cloudy and thundery weather.

If you’re viewing evening fireworks with family and friends, you might also want to enlighten them by pointing out some of the objects that will be sharing the spotlight with the skyrockets and Roman candles. Better yet, if you have a telescope, give them a show of a different kind: A close-up view of some celestial sights. What will be available to look at on July 4?

And just what was the state of astronomy back when our country was founded? What was in the early summer evening skies of 1776 as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and their contemporaries saw it? We’ll try to answer all of these questions here.

Moon takes center stage

Probably the most popular astronomical target for binoculars and telescopes is the moon. On Independence Day, the moon will already be favorably positioned more than halfway up in the southwest sky some 90 minutes before sundown. It will be a six-day old moon, meaning six days past new moon phase and only two days before it arrives at first quarter or “half” phase on July 6th.

Wait until the sky has become sufficiently dark and if you’re showing off the wide lunar crescent through a telescope, point out to your audience that the boundary zone separating the light and dark part of the moon is called the terminator and that the broad dark region on the moon’s bright side that is immediately adjacent to the terminator is Mare Tranquillitatis. This region, better known as the “Sea of Tranquility,” is where Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first human beings to set foot on our natural satellite on July 20, 1969. The moon will remain in view until it sets in the west around midnight.

Related: Earth’s Moon Phases, Monthly Lunar Cycles (Infographic)

Visible planets

After the moon, the next object most people will certainly want to see through a telescope is the ringed wonder of the solar system, Saturn. It appears to the naked eye as simply a bright yellowish-white “star” which will rise in the east-southeast at around 10:45 p.m. local daylight time.

However, it is probably best to wait a couple of hours to allow it to climb at least 20 degrees above the southeast horizon. The famous rings are visible in steadied (or image-stabilized) high-power binoculars and small spotting scopes, magnifying at least 25x. In a 3-inch telescope, the rings are readily seen when using an eyepiece magnifying 75x. With a 6-inch telescope at 150x, the view is stunning. With larger apertures and higher powers the sight – even for veteran amateur astronomers like myself – can be jaw dropping. I have never tired of showing off Saturn to those who have never seen it through a telescope. Usually, the comments range from “No way!” to “OMG!” And on not a few occasions, someone has accused me of showing a slide of Saturn when gazing through the eyepiece. Without question, Saturn is the planetary showpiece of the heavens.

A close second would be the king of the planets, Jupiter. It rises in the east a little before 12:30 a.m. local daylight time, but like Saturn, you’ll likely have to wait a couple of hours before it climbs high enough into a steady atmosphere to be seen well with an optical aid. It’s quite unmistakable visually, shining with a steady silvery glow some 16 times brighter than Saturn. In steadily held binoculars or a small telescope you’ll be able to see three of the four Galilean moons, all lined up on one side of Jupiter. Going outbound will be Io, Ganymede and Callisto. The fourth moon, Europa, will be in front of Jupiter appearing to transit its disk.

It’s not likely you’ll still find many people still lingering outside during the wee hours of the morning, but in case you do, you can point out Mars, a bright orange-yellow light hovering in the eastern sky soon after 3 a.m. Finally, Venus, the brightest of all the planets, will be poised low in the east-northeast horizon about 45 minutes before sunrise.

Related: The brightest planets in July’s night sky: How to see them (and when)

The starry skies of ‘76

Enough about this year’s July 4 skies. What did the nighttime skies look like on July 4th, 1776? The evening sky on that night was devoid of bright planets, save for just one: Saturn. At 9 p.m. local time as seen from Philadelphia, the ringed planet was visible about 20 degrees above the west-southwest horizon in the zodiacal constellation of Virgo. About 7 degrees to Saturn’s left was Virgo’s brightest star, bluish Spica. Due to rise in the east-northeast several minutes later would be a waning gibbous moon four days past full.

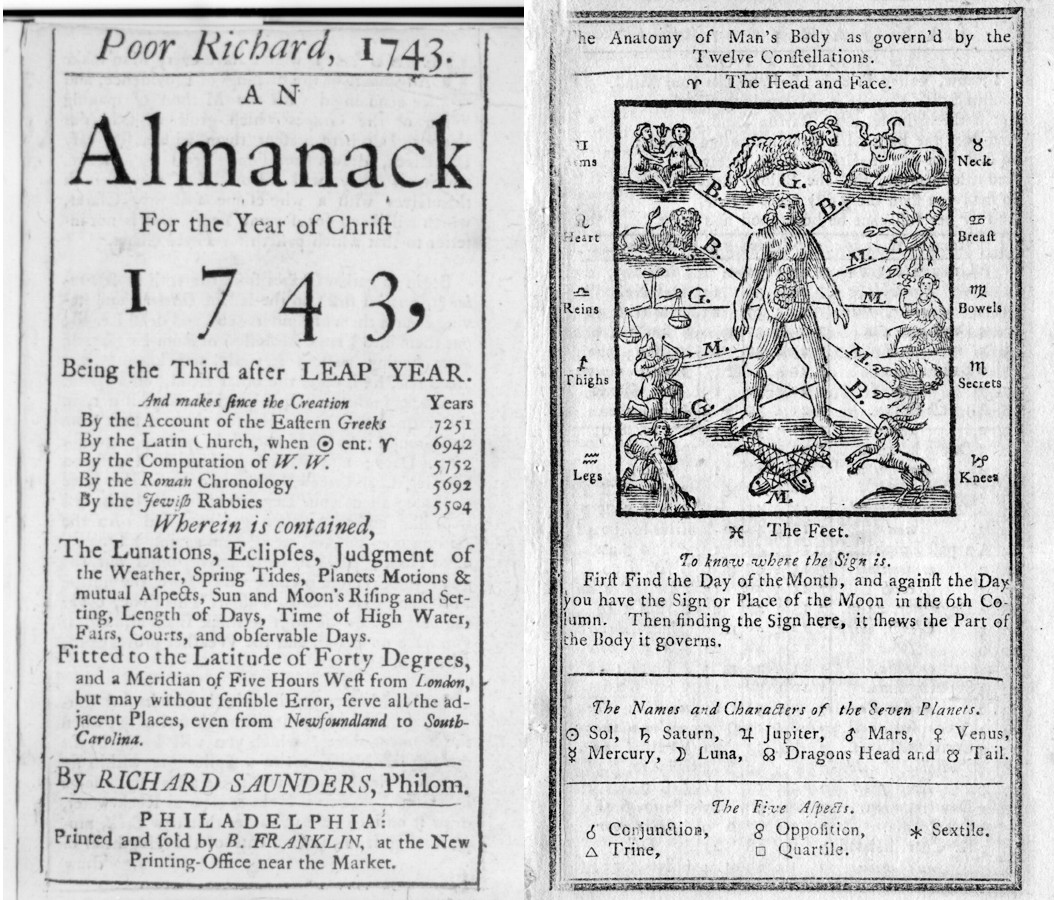

As for the other four bright planets, they were all positioned too close to the sun for observation on July 4th, 1776. If you owned an almanac at the time – and there was a good chance that you did – it might very well have indicated that Mercury, Venus, Mars and Jupiter were all “combust.” This was an oft-used 18th century term, indicating that a planet was too near to the vicinity of the sun, hence rendered invisible because of the sun’s light.

The role of almanacs

In the American colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries, the almanac was an important part of daily life. It gave the rising and setting times for the sun and moon, the times at which certain stars would culminate (reach their highest point above the horizon) on different days of the year, contained descriptions of the lunar phases, the aspects of the planets, some astrological lore, and Earth-based information such as the condition of the principal roads between cities. Typical almanacs even included tips on the care, cultivation, and breeding of crops and animals. All issues also contained a “Judgment of the Weather,” as the forecasts were called on the title page.

Two of the most popular almanacs of the 18th century were Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack from Philadelphia (Franklin adopted the pseudonym, “Richard Saunders”) and Nathaniel Ames’ Astronomical Diary from Boston. They each sold between 50,000 and 100,000 copies annually, in a country with a population of about 2.5 million. The Ames’ Diary was edited by a father and son team over a 50-year period from 1726 to 1775.

Astronomy was the elder Ames hobby, which is probably why his Diary was highly astronomical. He kept his fellow New Englanders informed of such coming events as transits of Mercury and Venus, and he spoke lavishly concerning Newton’s laws, recounted the history of the telescope and speculated on what the inhabitants of Jupiter might be like. When he died in 1764, his son, Nathaniel Jr., a Harvard graduate, continued the series until the demands of the Revolutionary War brought an end to the publication after the issue for 1775 had been printed.

Starlight dating to the time of Independence

Finally, we see many stars by light that started on their immense journeys before our country was born. Are there any whose light began toward Earth at the time of the signing of the Declaration of Independence? Because of the difficulty in measuring parallaxes, astronomers unfortunately cannot determine such distances with an accuracy of one light year. However, the Observer’s Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, in its table of 288 brightest stars, lists one that is above the horizon on July 4th that is 250 light years away. In fact, we have already mentioned it: Spica, in Virgo, ranked sixteenth among the 21 brightest stars.

The margin of error for Spica’s distance is plus or minus ten years, so it is just possible that if you gaze at Spica this year on July 4th, you might indeed be looking at starlight that dates back to the founding of the United States.

More likely, however, much ado will be made of this factoid in the year 2026, the year of the United States Semiquincentennial; the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence of the Thirteen Colonies in 1776.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook