Without a question of doubt, the term “meteor shower” is a misnomer. It creates a mental picture of shooting stars pouring out of the sky like water from a sprinkler, but that is simply not the case.

On a typical night, under a clear, dark sky you might count three or four meteors per hour. On certain nights, that count may climb to 15, 25, 50 per hour or more. That’s what astronomers call a “shower.” The mainstream media usually tell the general public to expect something spectacular, but often most — envisioning the “sprinkler effect” — are left disappointed.

A meteor storm is something else. In such cases, meteors will appear at rates of a thousand or more per hour and in a few rare cases, rates have been ten or even a hundred times greater than this!

How often do meteor storms occur? Here we provide a list of some of the greatest meteor displays dating back to the late 18th century.

Related: Meteor shower guide 2022: Dates and viewing advice

November 12, 1799: Grateful headache

Were it not for a headache, this spectacular display of Leonid meteors might have been missed altogether. It was Alexander von Humboldt — a writer-scientist-explorer of immense reputation in the 18th and 19th centuries who chronicled what happened.

He and his colleague, French botanist Aimé Bonpland, were located in Cumaná, Venezuela. On October 27, they had an encounter with a “Zambo,” a club-wielding native who gave Bonpland a concussion.

At 2:30 a.m. on November 12, despite a still aching head, Bonpland stepped outside to enjoy the freshness of the air. It was then that he noticed the most extraordinary, luminous meteors rising out of the sky from the east and northeast. He awakened Humboldt who wrote that “there was not a space in the heavens equal to three full moons which was not filled with bolides (exploding meteors) and falling stars.” The meteors left luminous traces that often lasted from seven to eight seconds.

Many of the shooting stars had a nucleus as large as Jupiter, from which darted sparks of vivid light. The display gradually ceased after four o’clock, although some falling stars could still be detected for fifteen minutes after sunrise.

April 20, 1803: An alarming downpour

Another spectacular storm of meteors that might have been missed, were it not for a fire alarm. The Lyrid meteor shower — hardly a rich display — move along in an orbit that strongly resembles Comet Thatcher of 1861.

There are several historic records of meteor displays believed to be Lyrids, notably in 687 B.C. and 15 B.C. in China, and A.D. 1136 in Korea when “many stars flew from the northeast.” But perhaps the most remarkable Lyrid shower occurred in 1803, when townspeople in Richmond, Virginia, were roused from their beds by a fire alarm and were able to view a very rich display between 1 and 3 o’clock. The meteors “seemed to fall from every point in the heavens, in such a manner as to resemble a shower of sky rockets.”

Related: 10 Earth impact craters you must see

(opens in new tab)

November 13, 1833: Starry snowfall

Often considered to be one of the most magnificent showers on record. Numerous reports across the United States described stars falling “as thick as snow coming down in a snow storm” Estimates as high as 20 per second were made. Many fell on their knees to pray; others feared the world was ending. Church bells were rung. People crowded the streets, afraid to remain at home.

Only with the dawn did the flashes fade away. Several observers noticed a definite pattern to their motion, radiating from a point near the star Gamma Leonis in the constellation Leo in such numbers as to make the sky in that direction resemble an umbrella. Recognition of this point, called the radiant, was one of the most notable astronomical discoveries of the nineteenth century. Previously, astronomers had regarded “shooting stars” as too trivial a phenomenon worthy of serious study, but now they could no longer be ignored. This amazing display marked the beginning of meteor astronomy.

November 14, 1866: European marvel

By now, astronomers had discovered that comets and meteor showers were connected; those particles released by comets along their orbits were encountered by the Earth upon crossing the comet’s orbit, creating a display of meteors.

The comet responsible for the Leonid meteors — Tempel-Tuttle — was discovered in December 1865 and orbits the sun about every 33 years. It was assumed that 33 years after their last great performance, another spectacular Leonid show would occur in 1866. And indeed, it did happen — but not for America. This time, Europe saw the firestorm.

One observer from Ireland later wrote, “It would be impossible to say how many thousands of meteors were seen, each one of which was bright enough to have elicited a note of admiration on any ordinary night.” But those who saw the Leonids of 1833 and 1866 said that the 1866 meteors — although magnificent — were far inferior to those that appeared in 1833.

November 14, 1867: Second time around

Another major Leonid shower appeared, this time over the United States. The single observer rate was perhaps 1,500 per hour. Not as abundant as the previous year, but according to the U.S. Naval Observatory, it was “the most brilliant seen in this country since the great shower of 1833.”

November 27, 1872: Rain of fire

(opens in new tab)

Biela’s Comet, which appeared late in 1845, had split in two since its last appearance six and a half years before. The new twin comets traveled close together. When these comets returned in 1852, one of the pair was very dim.

The comets were looked for again in 1858 and again in 1865 but were never seen again. But in 1872, as the Earth passed close to the orbit of the comet, its dusty remnants began striking Earth’s atmosphere. From Moncalieri, Italy, shortly after 8 p.m. local time, four observers described the meteors as resembling “a real rain of fire,” with meteors appearing at a rate of four per second. Others said the meteors were falling at rates too numerous to count. The meteors were described as slower than the Leonids and very faint. They seemed to emanate near a spot on the sky where the constellations of Cassiopeia, Perseus and Andromeda converged, so they became known as the “Andromedids,” or because the meteoroids were shed by Biela’s Comet they are sometimes referred to as “Bielids.”

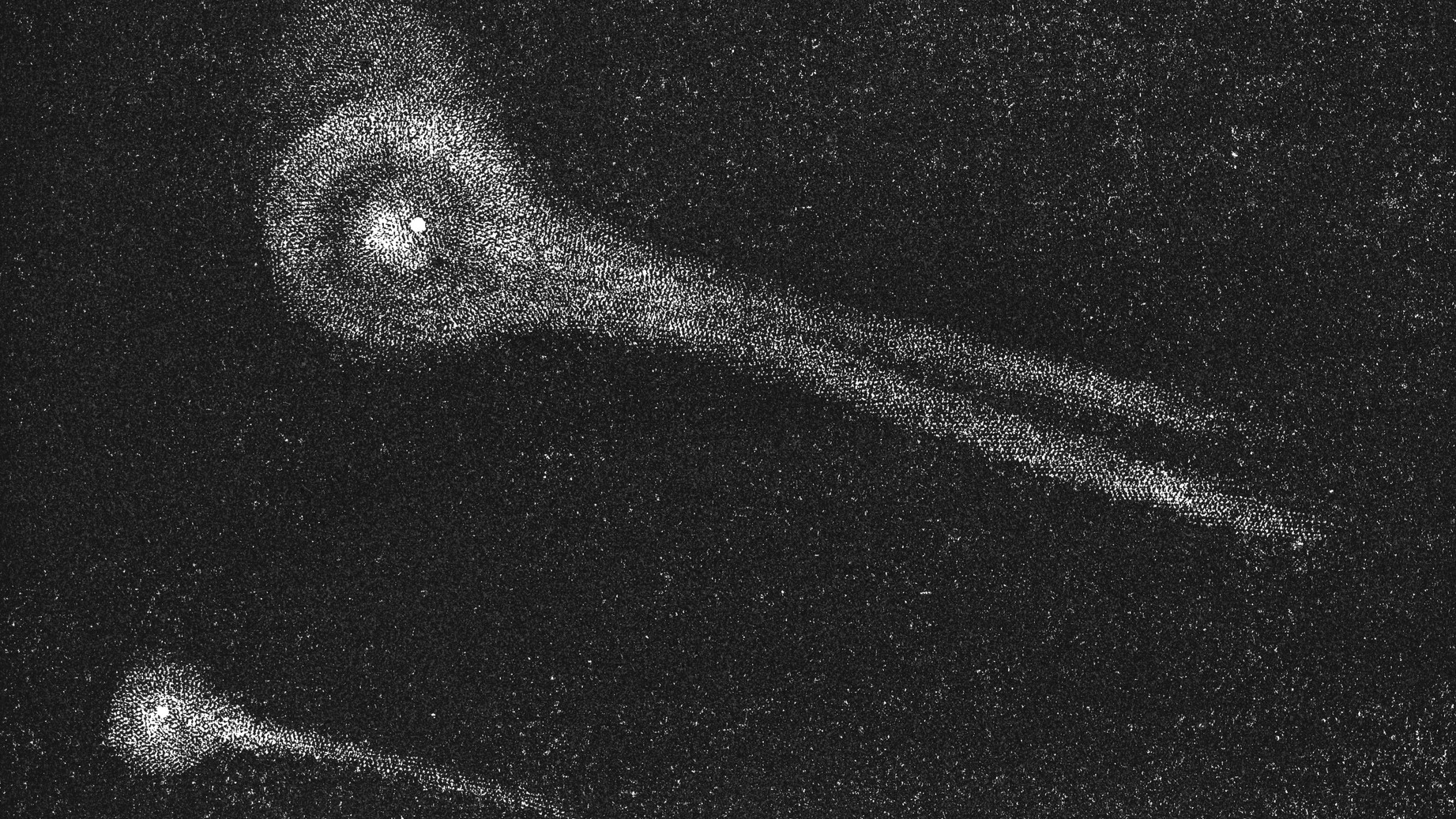

November 27, 1885: Dazzling trains

Thirteen years after the meteor storm of 1872, the Andromedids made a return appearance, with Europe again favorably placed to view them. One well-known British meteor observer commented that “meteors were falling so thickly as the night advanced that it became almost impossible to enumerate them.”

Other reputable observers stationed in Italy and France said the single observer rate reached over 200 per minute. From Scotland came the report that a large number of meteors “had brilliant phosphorescent trains, which continued to glow for several seconds after the meteors themselves had vanished.”

October 9, 1933: Surprise shower

(opens in new tab)

A history-making meteor storm occurred on this night over Europe when the Earth passed through the wake of periodic comet Giacobini-Zinner. This amazing display was unexpected and caught most astronomers completely off guard.

The New York Times reported that “A veritable rain of falling stars was visible over the whole of France and Belgium between 7 and 9 o’clock,” adding that “Residents of rural areas in Portugal, stricken by fear, started praying; some villages terrified.” From Ireland, the meteors “fell as frequently as snowflakes,” with rates at one point of 20 per second. An observer from Malta recorded a peak rate of 480 per minute.

The meteors appeared to dart from the head of the constellation of Draco the Dragon and were referred to as “Draconid” meteors, though others called them “Giacobinids” after their parent comet. They were described as slow, generally faint and were usually yellow.

October 9, 1946: Cosmic fireworks

Unlike in 1933, astronomers were ready for the Draconids in 1946. Comet Giacobini-Zinner was back and both it and the Earth seemed correctly positioned for a replay. Despite a full moon, skywatchers were not disappointed.

One correspondent for Sky & Telescope magazine wrote: “Three of us tried to keep count (of the meteors), but after tallying 500 ceased enumeration. There was no quarter of the heavens that was untouched by the fireworks.” From Chicago, another observer said that the brightest meteors outshone Venus at her best, and showed colors of red, orange, and green and could even be followed when their paths led behind wisps of clouds.

Hourly rates varied widely from as low as 3,000 to as high as 10,000.

November 17, 1966: Back from the dead

The Leonids were dead, they said. Indeed, they had not produced a meteor storm since 1867. The primary reason was that their source, Comet Tempel-Tuttle, made a close approach to Jupiter in 1898; the giant planet’s gravitational field threw both the comet and its trail of meteoroids off course.

So, in successive Leonid cycles in 1899 and 1932 the expected rich Leonid displays failed to appear. We were about ready to give up on the Leonids when they put on a stupendous display in 1966. From Kitt Peak Observatory in Arizona, one observer said some fireballs left trains that lasted up to 20 minutes. At the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Table Mountain Observatory in California, observers saw “a rain of meteors turn into a hail of meteors, finally becoming a storm of meteors too numerous to count.” At the peak, estimates ranged anywhere from 10 to an incredible 40 meteors per second!

(opens in new tab)

November 18, 1999: Short and sweet

A dramatic fusillade of Leonids sprayed from the Sickle of Leo across the starry sky as seen from the longitudes of Europe and the Middle East. The roughly hour-long outburst peaked at a rate of one or two meteors per second as seen by any given person. It was far short of the great Leonid storm of 1966, but it was an epochal spectacle nonetheless. This display contained a high proportion of faint meteors and a relative absence of fireballs.

November 18, 2001: Twin peaks

A most unusual setup as two Leonid peaks were forecast. The first, as Earth encountered material shed by Comet Tempel-Tuttle in 1766 favored North and Central America. Meteors came in bunches and clusters and were quite bright with hourly rates as high as 1,300 recorded.

Then came a second peak due to concentrations of material released by the comet in 1699 and 1866 which favored Australia and the Far East. That proved to be the more intense outburst, with numbers peaking at around 4,200 per hour. And from Massachusetts to Manchuria, everyone was impressed by the many fireballs that left long-enduring trains lasting up to several minutes.

November 19, 2002: A flick of the switch

Once again, a year with two Leonid peaks. Observers likened each outburst to a switch being turned on and off — suddenly there were lots of meteors and then abruptly, they were all but gone.

The first peak favored Europe; corrected single observer counts indicated a rate of about 2,300 per hour. The second peak favored North America where estimates indicated an hourly rate of about 2,700. But also, something of a disappointment thanks to the presence of a bright full moon and a relative dearth of bright meteors.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium (opens in new tab). He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine (opens in new tab), the Farmers’ Almanac (opens in new tab) and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).