Last month marks my 20th year writing the Night Sky column for Space.com. It is difficult for me to believe that in this forum I have penned over a thousand columns on a variety of different subjects covering space and stargazing.

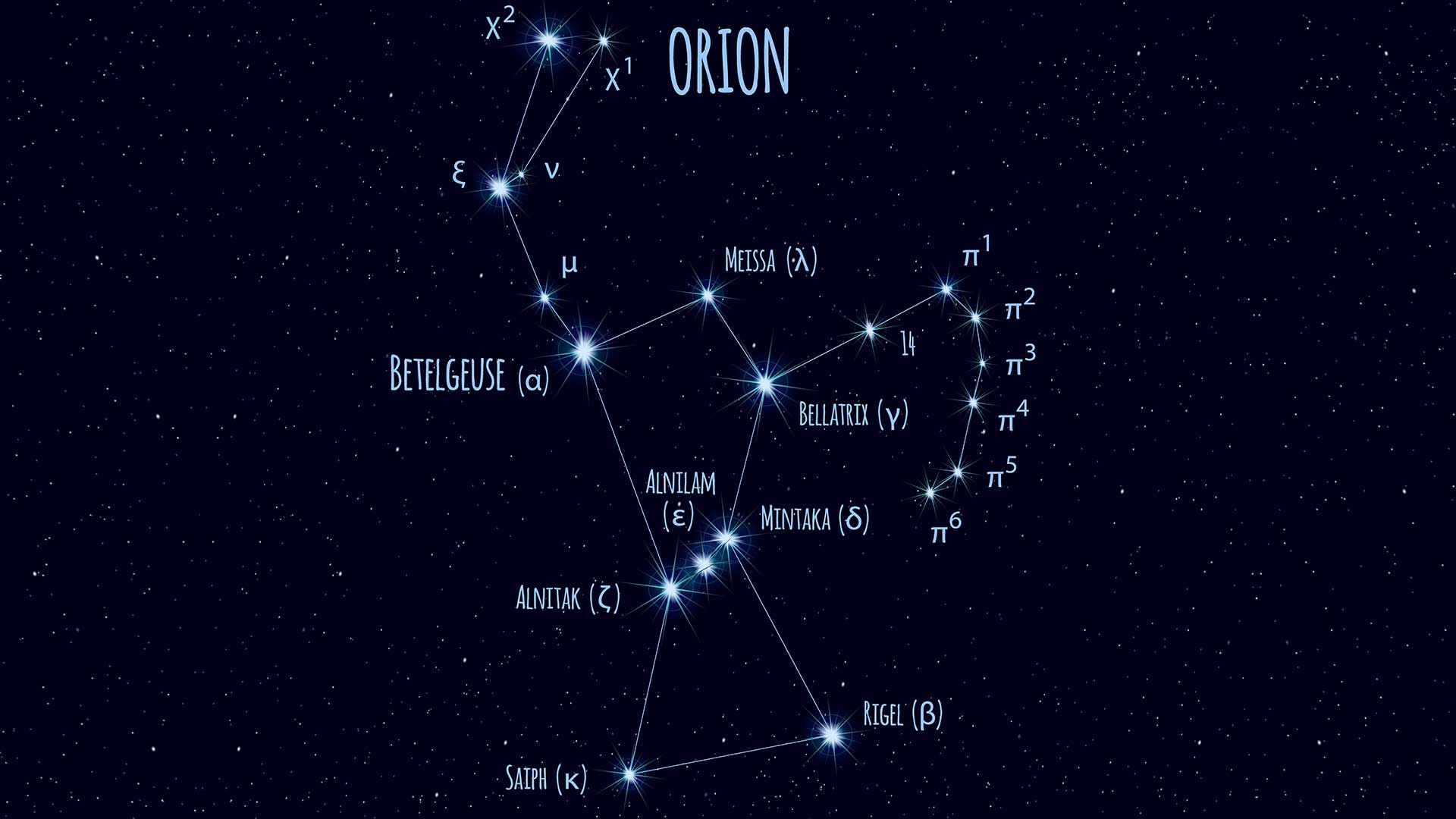

Among my constellation essays, I’ve probably written about the Orion constellation, the Hunter, more than any other and with good reason: No other star pattern can be compared to it. It has been recognized as perhaps the most eye-catching and extraordinary pattern of stars; a veritable treasure-trove of celestial wonders, containing two of the brightest stars, Rigel and Betelgeuse accompanied by its three belt stars in a distinctive diagonal row.

Related: Constellations of the western zodiac

Legends of Orion

Last month was most definitely the month of Orion; as the last bit of evening twilight fades away, we see him standing triumphantly high in the southern sky. There are numerous legends surrounding Orion. And there is more than one story of how he met his death. Orion liked to boast that no animal could ever escape him. This miffed the goddess Juno, so one day while Orion was pursuing a hare, she had a scorpion sting Orion on his heel, killing him.

This particular story was surely invented to account for the position, on opposite sides of the sky, of these two striking and easily recognized and very ancient constellations. When, on May evenings, the Scorpius constellation, the Scorpion, rises in the east-southeast, Orion quickly disappears below the western horizon, and not until the fall when Scorpius is setting does Orion appear again in the east. Hence it was thought that the mighty warrior was fleeing from his fatal adversary.

Other legends about Orion include the Chaldeans who know him as Tammuz, named after the month in which Orion’s familiar belt stars first rose before the sunrise. The Syrians referred to Orion as Al Jabbar, “The Giant.” To the ancient Egyptians he was Sahu, the soul of Osiris.

Related: Book reviews for three guides to the stars and constellations

In yet another story, Diana, goddess of the moon, fell in love with Orion and neglected her task of lighting the night sky, often preferring to follow him and leaving the night sky in darkness. Her twin brother, Apollo, the sun-god, was furious. Bad enough the chariot of the moon lay idle, but it was disgraceful that his sister fell in love with a mere mortal.

One afternoon, seeing Orion swimming far out at sea, he challenged his sister to hit what appeared to be no more than a dot among the waves. “Goddess of hunting you may be,” he taunted her, “but I wager you could not hit that faint, dark object there on the horizon.” Not realizing that this was Orion, Diana took dead aim with her bow and arrow and shot him.

Later, when Orion’s body washed up on the shore, she saw what she had done. Inconsolable, she placed his body in her chariot and drove to where the night was darkest and placed him into the sky — and suddenly the heavens were bright with stars. Diana also placed Orion’s hunting dogs to closely follow him and marked each with a brilliant star. Her grief also explains why the face of the moon, although so bright, appears so sad and cold.

The belt stars

The thing that makes Orion so unique among all the constellations is his belt of three, second magnitude stars. The trio — from lower-left to upper-right — are Alnitak, Alnilam and Mintaka. Many astronomy books refer to them as straight, bright and compact.

Certainly, they are bright and compact (extending across just 3 degrees of sky), but they’re not exactly straight. The middle star, Alnilam appears to ever-so-slightly sag compared to its companion stars that flank it.

Extending an imaginary line through the belt to the south and east will take you to the brightest star in the sky, blue-white Sirius, the Dog Star. Going in the opposite direction takes you to the V-shaped face of the Taurus constellation, the Bull, with orange Aldebaran marking the bull’s angry eye.

A tale of two stars

As we have previously noted, Orion contains two of the brightest stars in the sky. Blue-white Rigel (the ‘Left Leg of the Giant’), ranks seventh in terms of brightness rankings at magnitude +0.2. From mid-northern latitudes, Rigel when at its highest point in the southern sky is about at the same altitude above the horizon as Polaris, located diametrically opposite to it in the northern sky.

Located roughly 860 light-years away, Rigel is considered to be the most luminous star within 1,000 light-years of the sun. It’s a star literally burning the candle at both ends, shining at the prime of its life. It’s a true supergiant: a blazing white-hot star of intense brilliance and dazzling beauty, shining with a luminosity estimated to be roughly 120,000 times that of our sun.

Rigel is marginally brighter than the bright star marking the opposite side of Orion’s extremities, Betelgeuse (‘The Armpit of the Giant’). And yet, Betelgeuse seems to attract more attention because, in contrast, it shines with a cool, dull ruddy hue and is located 550 light-years away.

Recall that Betelgeuse was making headlines a couple of years ago because it had declined in brightness to such a degree that at one point it appeared to be shining at only half of its normal brightness (magnitude +1.6). It is an irregular pulsating supergiant star, nearing the end of its life and as such, it expands and contracts spasmodically and has been seen to get a dim as magnitude +1.1 to as bright as -0.1, brighter than the stars Rigel or nearby Capella.

The stellar incubator

But the true showpiece in Orion that continues to astound even veteran observers can be found hanging directly below Orion’s Belt, a trio of fainter stars, Orion’s sword, the middle of which appears to have a fuzziness surrounding it. But it is a telescopic view of that fuzz that will reveal a greenish-gray fan of nebulosity known as M42, the Great Orion Nebula.

Here you will find Theta1 (θ1) Orionis, better known as the Trapezium, four tiny bright stars in the heart of M42 that power the nebula. The light of the Orion Nebula is largely fluorescence, produced by the strong ultraviolet radiation from the high-temperature components of the Trapezium.

Located at a distance of 1,340 light-years from Earth, it is so large that it would take a beam of light 24 years to pass from one side of it to the other. In this time it would be traveling 11 million miles (17.6 million km) every minute of those 24 years.

Astrophysicists now believe that Orion Nebula is a stellar incubator; the primeval chaos from which star formation is presently underway. It is here where new stars are being born. Stars that will blow away their excess gaseous material when they fully radiate all of their energy, ultimately to shine in tomorrow’s sky for future generations to admire.

Truly, there is magnificence and excitement in the region that we know as Orion. One of the wonders of the nighttime sky.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook