The hottest commodity in astronomy these days is time — specifically, time using NASA’s brand-new, ultra-powerful observatory.

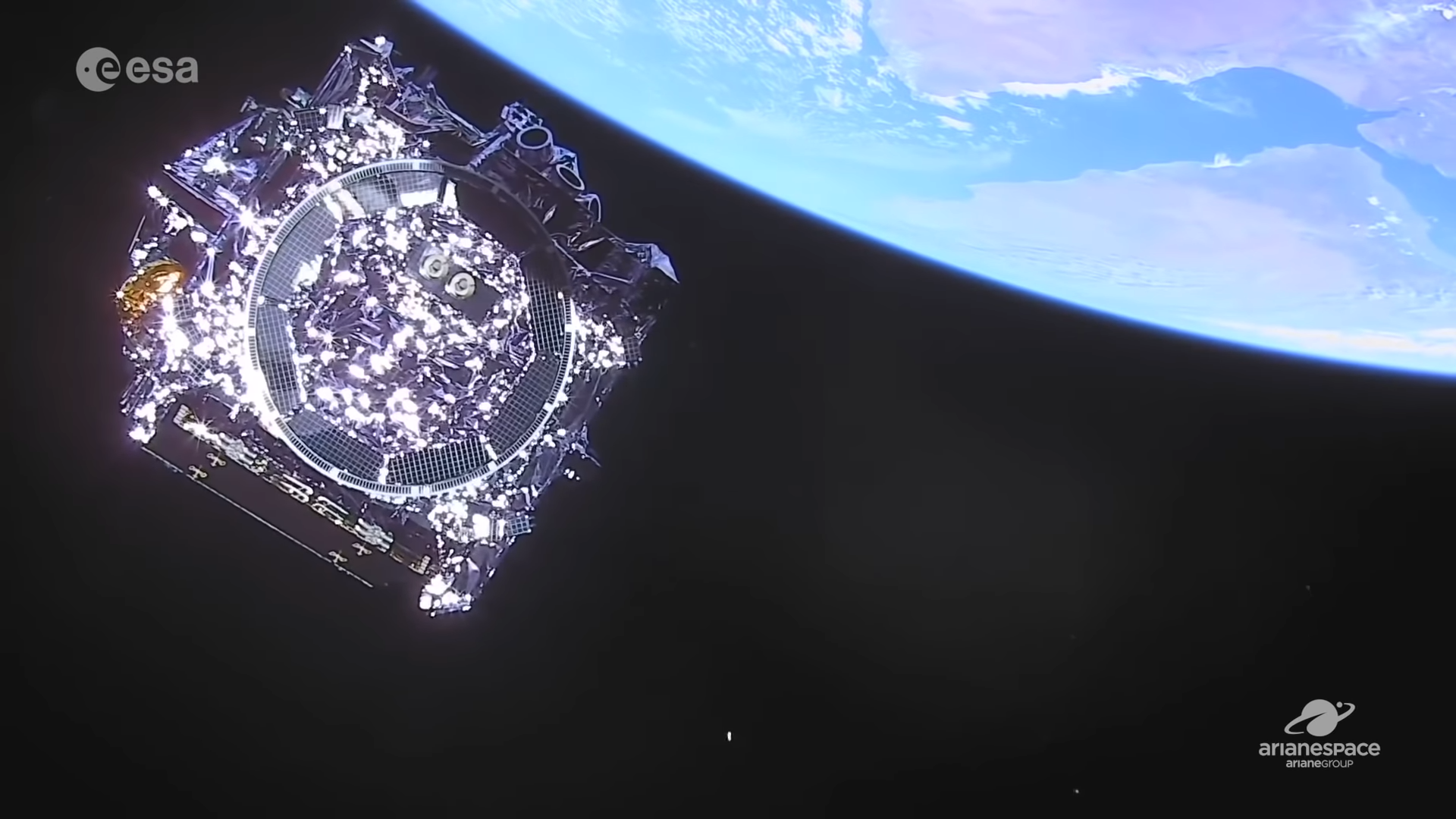

The James Webb Space Telescope, also known as JWST or Webb, launched on Dec. 25, 2021, and is scheduled to begin science observations by this summer. Astronomers eagerly await that moment: Scientists believe that the telescope’s sensitivity and infrared vision will give them data that helps them unravel countless mysteries of the cosmos.

And any data, from any instrument, is crucial to astronomers. “As an observational astronomer, I kind of live or die by what telescope time I get,” Larissa Markwardt, a Ph.D. student in astronomy at the University of Michigan, told Space.com. “It’s definitely hard to get established if you’re not getting any data.”

Live updates: NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope mission

Related: How the James Webb Space Telescope works in pictures

Markwardt led one of the 1,173 proposals that scientists around the world submitted in November 2020 arguing their case to use JWST. “In some ways it wasn’t as stressful” as other proposal submissions, Markwardt said. “I just assumed that I wouldn’t get the time, so I guess I was a little less fearful of submitting it.”

Markwardt and her colleagues wanted to use JWST to study rocks that orbit the sun at about the same distance as Neptune — one cluster ahead of the planet and one behind it. Scientists call this type of rock Trojan asteroids and believe that they contain some of the most primitive material in the solar system. Just last October, NASA launched the Lucy mission, dedicated to surveying the Trojan asteroids orbiting with Jupiter. But for Neptune’s companions, scientists are still stuck studying the rocks at a distance.

And Markwardt’s proposal, it turns out, was one of 266 projects awarded precious telescope time. During its first year of work, JWST will spend just over 24 hours studying nine different Neptune Trojans.

That’s a relief for Markwardt. “These objects are typically very faint, and so there wasn’t a ground-based telescope that could do these observations,” she said. “So really, we had to use James Webb or we couldn’t do this project at all.”

The Neptune Trojans project is one of 22 investigations that won the opportunity to use JWST to study objects in our solar system. Nearly every one of those projects is led by a full-fledged astronomer. But when teams of scientists were evaluating the flood of proposals to use JWST in its first year of science, no one knew who was an established astronomer and who, like Markwardt, was a graduate student.

That’s thanks to a system called dual-anonymous peer review, or DAPR, which hides the names of team members from expert reviewers and vice versa.

“I think that it’s very unlikely, if not impossible, that I would have gotten time on James Webb if it hadn’t been for DAPR,” Markwardt said. “This is something that everybody wanted to use, and I just can’t believe that they would give a little grad student like me the time.”

A bias in time

Telescope time is broken into a few categories: some time goes to the scientists who shepherded the observatory into being, some is saved for last-minute opportunities when something exciting appears in the sky. But the bulk of the time — 6,000 hours in Webb’s first year — goes to what’s called the general observer program, in which scientists from around the world make their case for using the observatory.

This year, scientists requested about 24,500 hours, so selection is key. General observer time is divvied up by a careful process in which more than a dozen anonymous panels of experts pore through proposals to determine what science should be prioritized.

The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore has been managing this process for the Hubble Space Telescope for decades and is now doing the same for Webb. “We started with a much simpler process,” Alessandra Aloisi, the head of the science mission office at STScI, told Space.com. “We didn’t have criteria defined; we would just tell the panelists, Score the proposal based on a scale from one to five, if you find it interesting, exciting, transformational.”

But in the 2010s, someone asked whether STScI knew how the proposals of male and female astronomers fared. The Institute didn’t; it legally isn’t permitted to collect demographic data with proposals, Aloisi and her colleagues emphasize. But the science office was still intrigued. Neill Reid, now associate director of science at STScI, decided to look into it, analyzing a decade’s worth of Hubble proposals that displayed the principal investigator’s name on the first page.

The numbers were stark. Reid found that in every one of those years, proposals led by a male principal investigator were more likely to win time than proposals led by a female PI. In a couple of years, women’s success rates were nearly equal to men’s; in some, men were nearly twice as likely to end up with Hubble time. For some years, Reid analyzed additional data to see whether factors like career stage or scientific subfield made a difference; still, men’s proposals were on the whole more likely to win time.

“A lot of people were saying, Well, we kind of thought this was going on,” Reid told Space.com. “I don’t think it was unexpected, but the fact that it was so obvious I think was something of a shock.”

The Institute thought it had a real opportunity to change the system. Overall, astronomers have far too many ideas for using the Hubble Space Telescope than the instrument can ever execute, and STScI has more flexibility to experiment than, say, NASA might. STScI decided to see whether it could even the numbers by, for example, moving the principal investigator’s name from the first page of the proposal to the second or by listing all team members in alphabetical order instead of highlighting the lead researcher.

But these approaches didn’t work.

“It just wasn’t really changing minds or changing attitudes toward proposals,” Lou Strolger, who was chair of the working group formed to reduce bias in time allocations and is now the deputy head of the instruments division at STScI, told Space.com. “People were still talking about them in terms of ‘Jennifer’s proposal’ or ‘Matthew’s efforts’; it was very clear that they were talking about the proposal and the identity synonymously, and that was just not what we wanted to do.”

So Reid recruited support. “Scientists always think we can do things by ourselves,” he said. “We got to the point where we said, Look, we actually need to bring in people who are experts in this area.”

A new approach

STScI brought in social scientists to advise on review processes and eventually decided to take a leap and try not providing panelists with researchers’ names at all.

“We had a pretty good inkling that it was going to be contentious to begin with,” Strolger said.

And it was. “As you can imagine, it split the community right in half, and in many cases it went across age lines,” Strolger said. “There were many who thought that this was very much the right thing to do; they long suspected that there was bias in the process and that this was a great move toward reducing that bias. There were other people who were like, ‘I spent a career building a reputation for myself, and you’re essentially removing that power from me.'”

But in 2018, Hubble’s first proposal cycle under the dual-anonymous system opened.

The institute did build a loophole of sorts into the system to try to assuage scientists’ concerns. “There was some worry in the community that, well, what if we get somebody putting in a proposal that just was not qualified at all,” Reid said. So after the anonymized proposals are ranked, panelists can check the scientists they’ve selected and make sure they’re qualified. “We’ve never had them say, ‘You can’t give these people time,’ so I think that kind of reassures the community, it’s reassured NASA, that this process is not bringing in kind of crazy people to use the telescopes.”

It wasn’t just scientists who wanted to use Hubble who had to adjust; the scientists evaluating proposals did, too. Aloisi said many were skeptical going into the first dual-anonymous discussions, but they eventually came around to the new process.

“They said that they felt relieved because they were just talking about science, not about the teams,” she said. “They described it as liberating because they could just focus on the best science.”

And the approach has evened acceptance rates between proposals led by men and those led by women; one year, women were more likely to win time than their male counterparts.

Now, dual-anonymous is the default for STScI — it’s built into the software behind the proposal review system — and Webb was inevitably going to use the same approach. “For JWST, it was not even questioned,” Aloisi said.

Into the future

Dual-anonymous proposal review is still new to the astronomy community, but the concept has taken the field by storm as scientists of all stripes confront the reality of implicit bias. Since Hubble switched to dual-anonymous, NASA’s astrophysics division decided to adopt the system as well, and STScI has fielded inquiries from far and wide about how to adapt the approach.

“I was somewhat expecting that the other observatories would come asking how we do these sorts of things, and that’s exactly what happened,” Strolger said. “But I wasn’t expecting to get phone calls from particle accelerator centers asking how you do this and how did you convince your community that it was worth doing?”

There’s only so much that STScI can conclude about the efficacy of the policy without being allowed to collect demographic data with proposals; even the gender analyses are flawed since they have been conducted based on apparent gender rather than self-reported identity.

For the future, the institute is considering developing a system that would see an independent third party collect and analyze demographics, with only the overall statistics shared with the science office. Those statistics would let the institute check for bias along other characteristics. “Gender is just the tip of the iceberg,” Aloisi said.

But one trait that outsiders can identify easily is their career stage, either by identifying the year a scientist earned their Ph.D. or by checking whether they were first-time observers with STScI. And although gender data initially motivated the switch to dual-anonymous, STScI has seen a bigger impact on new principal investigators and early-career researchers like Markwardt, who are proposing at much higher rates than they did under the old system.

“We have changed the attitudes of those who were interested in proposing for time such that they didn’t feel that they needed to have notoriety in order to be eligible for time,” Strolger said, calling it “the real measure of success” for the initiative.

Astronomers are still learning to trust the new process even when it turns down their proposals. Markwardt said that while no one has confronted her directly, she knows some of her colleagues may quietly doubt her ability to make good use of her precious 24 hours of JWST time.

“There’s this feeling of, ‘You only got the time because they’re trying to let in more people that are marginalized,'” Markwardt said. “But I wrote a really good proposal; that’s why I got the time. It just happened that my name wasn’t on it so that they couldn’t make extra assumptions or judgments about my work.”

That’s the sort of opportunity she wants to see open to anyone. “If you can dream up the science, then I think you should have the chance to be able to do it,” Markwardt said.

Email Meghan Bartels at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.