With NASA’s Artemis 1 mission launching to the moon this month, Space.com is taking a look at what we know about the moon and why we care. Join us for our Moon Week special report in the countdown to Artemis 1.

Some 4.5 billion years ago, a Mars-size celestial body named Theia slammed into a young, molten Earth, nearly decimating the planet. But from the debris created by this cataclysm, a new Earth formed — and so did our moon. (Or so the current leading theory of lunar formation goes, anyway.)

When humanity finally came around, the moon became an object of our utmost fascination. As a constantly present yet ever-changing object in the sky, it’s no surprise that ancient cultures around the world were curious about the moon, incorporating it into all sorts of myths and legends. From the Greek goddess Selene to the Chinese goddess Chang’e, lunar deities are commonplace throughout human history.

But ancient cultures also considered the moon a practical tool. While the rising and setting of the sun denote the passing of a single day, the lunar cycle takes place over 29.5 days, or roughly a month. Naturally, it’s a helpful way to gauge the passing of time. Many North American indigenous peoples, for instance, named each of the full moons for its associated seasonal phenomena, from the blooms and harvests of flora to the behavior of fauna. And we still use those names today.

Related: The ultimate guide to observing the moon

Though there is evidence of ancient astronomers contemplating the moon — Greek philosopher Anaxagoras hypothesized that the moon was rocky and Earth-like in the fifth century B.C. — the modern era of astronomy began with the development of the telescope in the 17th century. That invention opened the doors for deeper curiosity about the moon.

The first telescopes weren’t particularly powerful — Galileo‘s first had only 3x magnification. Because the moon is the closest celestial body to us, it’s the easiest to study with less powerful telescopes, and so, from the 17th to the early 20th century, the moon was a major focus for astronomers, who drew maps of its surface and eventually even photographed it.

During this period, science fiction even indulged in some lunar fun. In the 16th century, Johannes Kepler penned the novel “Somnium,” a sort of proto-sci-fi work that explored what the Earth might look like from the moon. Cyrano de Bergerac then wrote “The Other World: The Comical History of the States and Empires of the World of the Moon,” in which the main character, also named Cyrano, attempts to fly to the moon to meet its inhabitants. By 1902, sci-fi moved from the written word to the silver screen with Georges Méliès’ film “Le voyage dans la lune,” or “a trip to the moon.”

Fiction then became reality during the space race. Although the heated competition between the United States and the then-Soviet Union had its roots in ballistic missile–based nuclear warfare, the goals soon expanded to spaceflight, culminating with Sputnik making history as the first artificial satellite in 1957, and eventually to the U.S. moon landing in 1969. The fascination with the moon during this period was rooted in national pride and human achievement.

NASA’s Apollo program became a global phenomenon — when Apollo 11 landed on the moon in 1969, an estimated 650 million people tuned in to the televised broadcast, according to NASA. The five additional Apollo missions that followed ignited a new obsession with the moon and enabled new science by bringing moon rocks into laboratories on Earth.

A few of those rocks have had more dramatic adventures. The U.S. government gave away a portion of the Apollo astronauts’ haul as diplomatic gifts to states and nations, but decades later, up to 150 of those are missing.

“Some are so enthralled by possessing something brought back by mankind from space that they are willing to steal it, to possess it,” Joseph Gutheinz, an attorney who once served as an undercover agent for NASA to recover stolen moon rocks, told Space.com.

After the Apollo era, the obsession with the moon fizzled out to some extent, particularly as NASA focused on other avenues of space exploration and research, like the International Space Station (ISS) and Mars rovers.

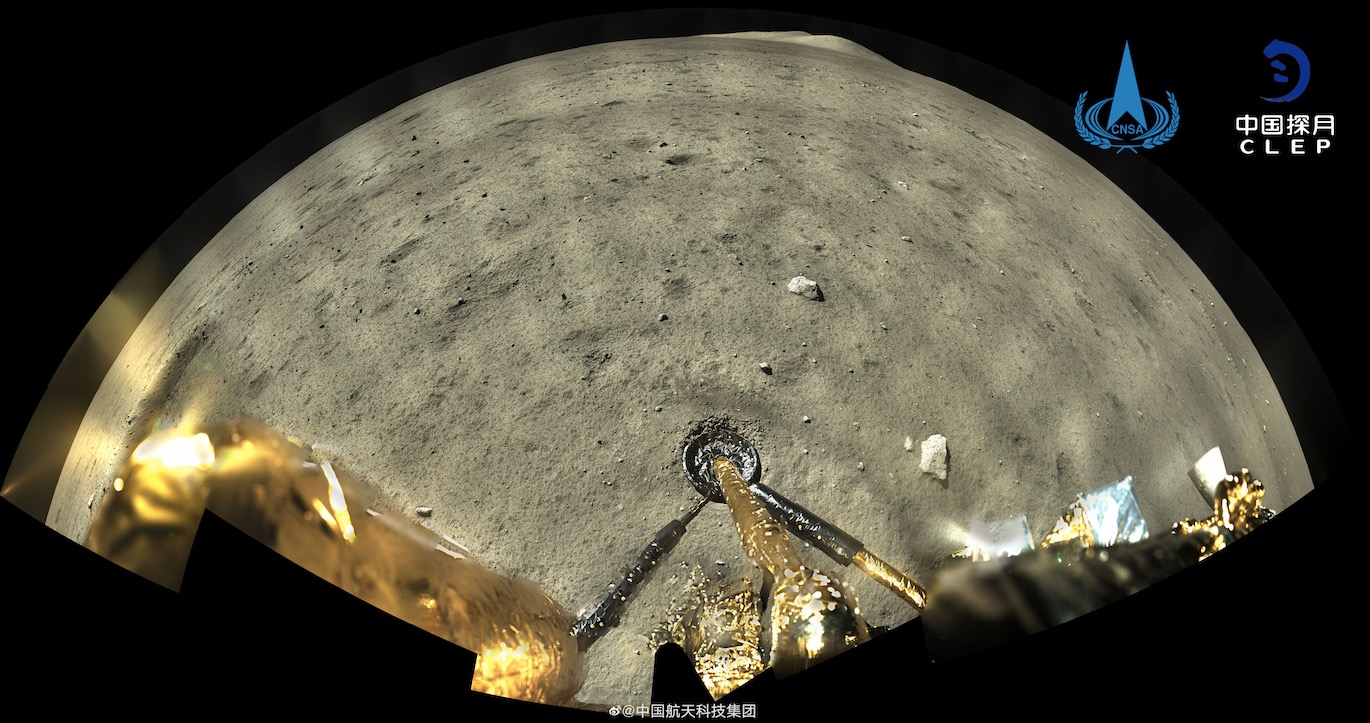

But now, there’s a renewed interest in the moon, not only in the United States, but in countries around the world. Two nations currently have spacecraft on the lunar surface or in orbit: China operates two landers, as well as the Yutu-2 rover on the far side of the moon, while India’s Chandrayaan-2 spacecraft is in orbit. South Korea’s Danuri orbiter is en route to the moon now, and several more countries plan to launch moon missions in the coming years, including Japan, Russia and the United Arab Emirates.

NASA, too, is returning to the site of one of its greatest achievements. Its Artemis 1 mission is scheduled to launch Aug. 29 and will herald a new era of lunar infatuation. Although this mission is uncrewed, astronauts will fly on Artemis 2; Artemis 3 will return humans to the moon for the first time since Apollo 17 departed in 1972.

And this time, we’ll be staying for good: NASA intends to build a permanent base on the moon, as well as an orbiting station called the lunar Gateway, which will be a launch point for new crewed missions to deep space, including Mars in the coming decades.

“The moon is a source of wonderment for most,” Gutheinz said. “Just out of our collective grasp, save for a few, it is a harsh lifeless world akin to a blank canvas. A canvas waiting for the artist’s touch.”

With the Artemis program underway, those artists are preparing their brushes.

Follow Stefanie Waldek on Twitter @StefanieWaldek. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.