CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — It’s make or break time for NASA’s new moon rocket.

With 8.8 million pounds of thrust, the rocket — called the Space Launch System (SLS) — is designed to be mightier than NASA’s mighty Saturn V. Its Orion space capsule outsizes its Apollo ancestor by one-third. Yet neither spacecraft has passed the ultimate test: a trip to the moon and back.

That will change Monday (Aug. 29), when NASA aims to launch the SLS megarocket and Orion on Artemis 1, a test flight that serves as the vanguard of the agency’s Artemis program to return astronauts to the moon by 2025. Liftoff is set for 8:33 a.m. EDT (1233 GMT) from Pad 39B here at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. You can watch the launch live online Monday starting at at 6:30 a.m. EDT (1030 GMT).

“Our zero hour approaches for the Artemis generation,” Mike Sarafin, NASA’s Artemis 1 mission manager, told reporters here Saturday. “We do have a heightened sense of anticipation.”

Related: NASA’s Artemis 1 moon mission: Live updates

More: 10 wild facts about the Artemis 1 moon mission

That anticipation is not something NASA owns alone. Up 200,000 spectators are expected (opens in new tab) to flood Florida’s Space Coast here to catch a glimpse of NASA’s first moon rocket to fly in over 50 years. Their hopes mirror NASA’s for a successful mission where success is far from certain.

“This is a very risky mission,” said Jim Free, NASA’s associate director for exploration systems development. “We do have a lot of things that could go wrong during the mission in places where we may come home early, or we may have to have to abort to come home.”

In fact, the mission may not launch at all.

“Our potential outcomes on Monday are that we can go within the window, or we could scrub for any number of reasons,” Sarafin said. “We’re not going to promise that we’re going to get off on Monday.”

NASA has a two-hour window in which to try and launch Artemis 1 on Monday that closes at 10:33 a.m. EDT (1433 GMT). There is a 70% chance of good weather during that time, NASA has said.

Video: Lightning strikes Artemis 1 launch pad days before liftoff

A long road to the launch pad

NASA has been trying to build a giant new rocket for nearly two decades. In 2004, the agency announced plans for a massive rocket, then called the Ares V, as part of its Constellation program to return to the moon by 2020. That program was ultimately canceled, replaced by what has become the Artemis program, though the Orion spacecraft did survive the transition. The five-segment solid rocket boosters (a bit larger than those used on NASA’s shuttle program), originally part of Constellation’s Ares 1 rocket to launch Orion, also found new life in the SLS.

“We’ve been through our challenges, just like every other piece of this whole rocket,” Bruce Tiller, NASA’s manager for the SLS boosters, told Space.com in an interview. “Everybody’s had their challenges that they’ve overcome over those years. And now I think we’re as ready to go as we can be. And it’s just really exciting.”

Congress directed NASA to build the Space Launch System over a decade ago, calling on the agency to use shuttle-legacy hardware like the solid rocket boosters and RS-25 core engines derived to build a new vehicle for deep space exploration. The first test flight was targeted for 2017 at the time. It is way behind schedule.

“I would say simply that space is hard,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, who was in the Senate as a Florida senator when SLS was approved, said Saturday on what the agency has learned over time. “You are developing new systems, and it takes money and it takes time.”

Simple, but aggressive goals

NASA has “very simple, but aggressive” goals for Artemis 1, Free said.

First, the mission must test Orion’s heat shield to make sure it can survive the 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,800 degrees Celsius) temperatures of reentry when it returns from the moon at 25,000 mph (40,000 kph). NASA also wants to make sure SLS delivers Orion into its lunar orbit to see how the spacecraft, which has a service module built by Airbus and provided by the European Space Agency, performs in deep space.

The space agency also wants to recover the capsule after it splashes down in the Pacific Ocean to see how it fared overall. It is carrying over 1,000 sensors to record every facet of the flight, NASA has said.

At its farthest point from Earth, Orion will be 290,000 miles from our planet and 40,000 miles beyond the moon — the farthest a crew-rated capsule will have visited to date (breaking a record set by the Apollo 13 crew in 1970). Its 42-day mission is much longer than the 10 days a crewed flight would be, NASA has said.

Despite its length, the mission is expected to complete just one and a half orbits of the moon as it flies in a long, looping orbit in the opposite direction of the moon’s path around Earth. That “distant retrograde orbit” will bring Orion as close as about 60 miles (97 km) and as far out as 40,000 miles, mission managers have said.

Inside Orion is a spacesuit-clad “Moonikin” mannequin and humanoid torsos covered in sensors to measure the radiation environment Artemis astronauts will have to endure. And perhaps the most important test: reentry, when Orion will slam into Earth’s atmosphere, skip off a tiny bit, then plunge back down for what NASA calls a “skip reentry.”

“We are pushing the vehicle to its limits, really stressing it to get ready for crew,” Sarafin has said.

There are some science goals, too. The Artemis 1 mission includes 10 small cubesats to test technologies for deep space exploration. One, called NEA Scout, will use a solar sail to leave the moon in search of a small asteroid while the others are expected to support Artemis projects near the moon.

“Some of them are testing technology for navigating in deep space. We even have one that’s traveling farther out, going to encounter an asteroid,” said Jacob Bleacher, chief exploration scientist at NASA’s Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate. “But some of them will be focusing more on the moon making measurements of the movement, in fact mapping where some of the water deposits might be.”

Astronauts back to the moon

If all goes well on Artemis 1, NASA will follow it up with Artemis 2, a crewed flight that will send four astronauts on a flyby mission around the moon in 2024. The time-lag between missions is partly to wait and see how Orion performs and also so NASA can use some of the avionics and other components on Artemis 1 on the crewed flight.

And if that Artemis 2 mission succeeds, NASA hopes to follow it up with its first crewed moon landing of the 21st century on Artemis 3 in 2025. That moon landing, which would send two astronauts — including the first woman on the moon — to the lunar south pole, does depend on factors beyond SLS and Orion.

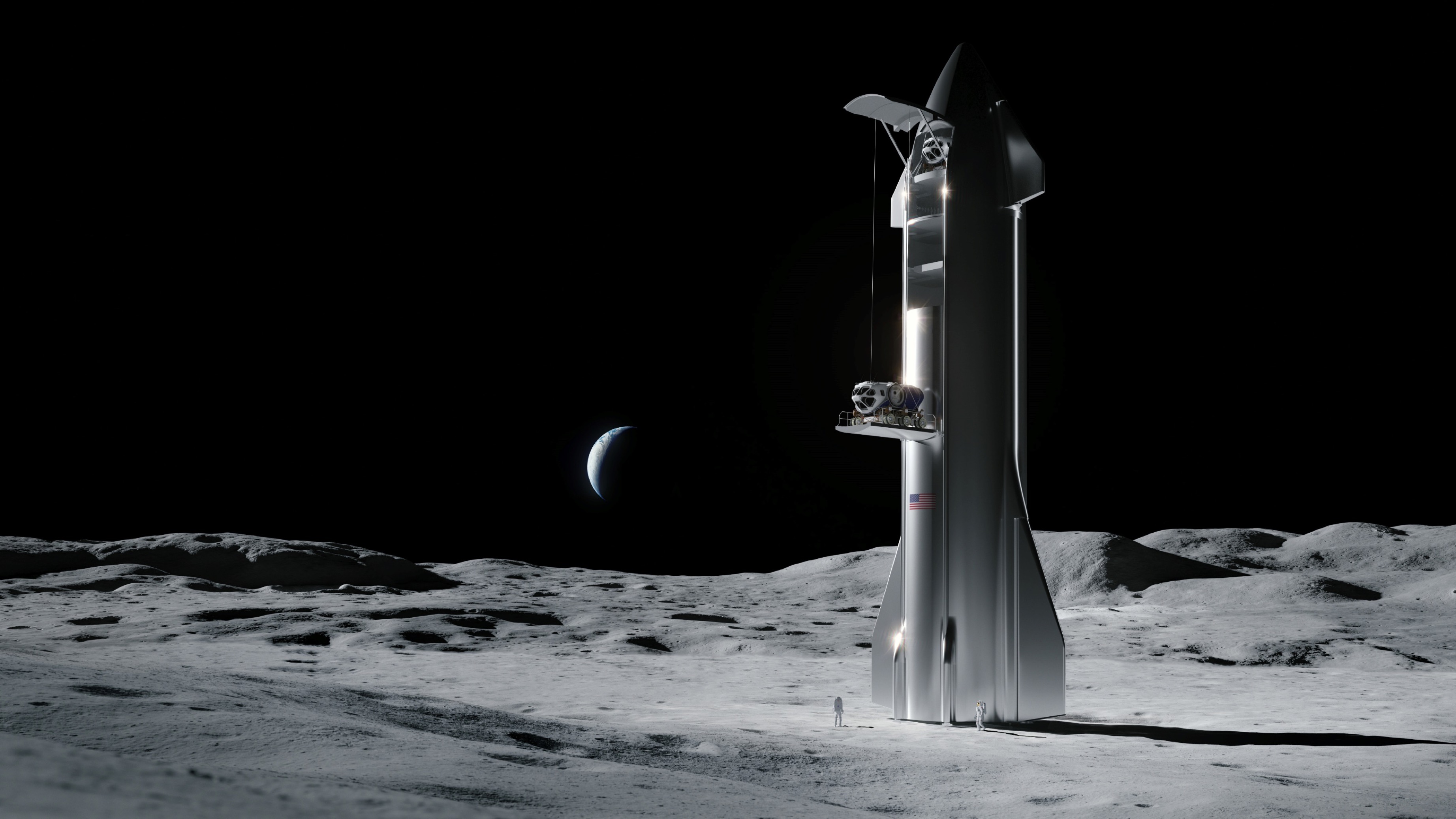

NASA needs new spacesuits and a huge lander to complete the Artemis 3 mission. SpaceX is building a massive Starship moon lander for NASA while other companies are developing Artemis spacesuits. If either component is late, it will impact the agency’s plans.

“If our suits aren’t ready, we’re not going to land on the moon and the inverse is the same, if our suits are ready and Starship isn’t,” Free said.

But NASA stresses it is committed to returning to the moon in a sustainable way that isn’t just footprints, flags and photos. The agency has already built hardware for Artemis 2 and future SLS boosters, with plans through at least Artemis 9.

NASA has doled out contracts to build components of a new Gateway space station around the moon to serve as a staging ground for lunar landings. And the ever-present target is Mars, which Nelson said NASA is targeting for crewed landing sometime in the late 2030s.

“There’s a big, big universe out there to explore,” Nelson said. “This is the next step in that exploration and this time we go with our international partners.”

Email Tariq Malik at [email protected] or follow him @tariqjmalik. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Instagram.